生活記憶博物館:一個菲律賓華人家族的故事

作者∕照片:Marina Yap(前 ICOM 國家委員會事務專員) 編輯:田偲妤

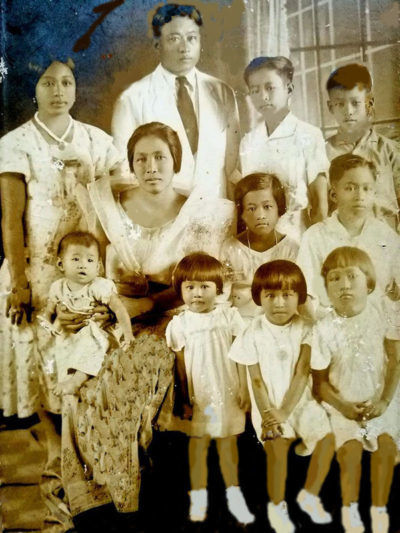

這是一篇菲律賓華人家族的口述歷史,Marina Yap是一名有華人血統的菲律賓人,她的曾祖父來自中國廈門,靠著出口菲律賓農特產致富,他的祖父還曾擔任過地方的副市長,捐地蓋醫院、提供難民庇護所與物資、創建中文學校。在閱讀這篇文章時,建議各位想像自己正坐在一個菲律賓家庭裡,看著一張張珍貴的家族照片,傾聽菲律賓朋友娓娓道來祖先飄洋過海到新天地發展的故事。

前言:

在開始這段看似平凡卻充滿生命力的故事前,我們有必要先來認識故事的場景—菲律賓,這個與臺灣隔著巴士海峽相望的島國,其命運與臺灣頗為相似。早在數萬年前的舊石器時代即有人類在島上活動,這些人與臺灣的原住民同為南島語族,並於3世紀起即與亞洲各國有貿易往來,中國商人帶來絲織品和瓷器、印度人帶來梵語文化、阿拉伯和波斯人帶來貿易與宗教。16、17世紀的大航海時代,野心勃勃的歐洲人來到遠東尋找香料、茶葉、瓷器等物產,1521年麥哲倫率領西班牙探險隊首次抵達菲律賓,從此開啟了菲律賓長達四個世紀的殖民史,先後經歷西班牙、美國、日本的統治。

位於海陸交通要道上的菲律賓自古即是不同民族的必爭之地,這裡的「爭」並非只能用霸權的觀點來詮釋,如果回到人類最基本的需求,爭的未必是權力,更多的是生存的機會。故事中於1870年代從中國來到菲律賓宿霧發展的葉家祖先就是其中一例,更是廣大華人移民的縮影。早年的華人移民心懷我們難以想像的冒險犯難精神,赤手空拳來到異地墾荒,不僅帶入中華文化,更與當地文化結合,形成與它地全然不同且彌足珍貴的菲律賓華人文化襲產。百年前的華人祖先秉持不忘根本又包容異己的胸襟來到菲律賓,如今他們的子子孫孫也延續著祖先的精神,在食物、教育、節慶等文化中隨處可見中華文化的影子,彷彿一座座尚在呼吸、成長的無形博物館,追本溯源、開枝散葉。

飄洋過海的葉氏家族:我的曾祖父克里桑托葉(桑托爺)

1870年代,我的曾祖父克里桑托葉(我們稱他為桑托爺)從中國大陸來到菲律賓宿霧省的布果市。據信當時他與其他七名兄弟同來,其中兩名兄弟在家族裡眾人知曉的名字是Intsik Kiga和Intsik Barresto。後者與桑托爺一起定居在布果市,老四住在距布果市不遠的班塔延島。其他兄弟則散居於菲律賓各地,不幸的是其他兄弟從此沒了彼此的音訊。桑托爺的家族起源於河南省,但後來遷徙到廈門。當我們還很小的時候,我的祖父曾向我們提及,家族中還待在中國的成員許多在清朝帝國軍隊中擔任將軍職位。

根據同行旅客為桑托爺繪製的畫像來看,他當時還穿著「長衫」,長衫原本是滿族男性服飾,後來成為所有漢族中國人在清朝時的統一服裝。桑托爺抵達菲律賓時,也同樣有著薙頭並蓄著傳統長辮的髮型。

在布果市定居後,桑托爺娶了當地原住民與西班牙混血後裔約瑟芬宜亞安(我們稱她為瑟帕婆)。由於當時菲律賓是西班牙殖民地,根據天主教律法,在婚後桑托爺必須改信天主教。改信天主教後,他將名字改為克里桑托葉,保留了葉這個姓氏。可惜的是,因為相關記錄都已在二戰期間被燒毀,目前找不到任何檔案記錄他的完整中文姓名。

桑托爺的岳父安傑宜亞安在1886-1887年間,擔任布果市市長(gobernadorcillo),主要掌管該區果樹與甘蔗的種植。事實上,在他任期內出現了對於黑砂糖需求量大增的情況。桑托爺的事業則是出口椰子和龍舌蘭纖維,因為出口生意興旺,讓他有能力在布果市不同區域的合適城鎮購置地產,並買下一千公頃左右的農田,用來種植甘蔗。

桑托爺和瑟帕婆生了五名子女:尤吉尼歐(吉尼歐爺)、艾斯特邦(特邦爺)、潔辛塔和荷蒙吉娜(雙胞胎)、班奈狄塔。我的祖父是長子吉尼歐爺,他和弟弟特邦爺被送回廈門學習中國語言和文化(主要是福建話和國語)。他們待在廈門十年,與桑托爺的家族同住。被迫與兩個兒子分開的瑟帕婆非常傷心,時常哭泣,為了讓她排遣寂寞,又知道她嗜賭(像她沉迷於菲律賓賭博遊戲「漢塔克」(hantak)),桑托爺就在他們住的城鎮附近的地產上,蓋了一座賭場和一間大型鬥雞場。

他們的房子佔地約兩千三百平方公尺,依西班牙風格樣式建築,位於小丘陵上。部分山坡被夷平,地基平穩後,房子的牆便倚山而建。整棟建築物包括地板全以硬木建造,包括硬度極高的珍貴木材:菲律賓合歡木、印度紫檀木和米特克斯木。一樓被當成店面與儲藏室使用,來販售椰子和龍舌蘭纖維。一樓到二樓間有四米高,從一樓要爬到二樓生活區的三間房間、客廳和廚房,至少要爬二十四階樓梯(又分成六階與十八階)。每間房間佔地兩百平方公尺。傢俱也是採用西班牙風格,而窗玻璃則由雲母蛤打造。緊鄰客廳有一道通向大露臺的門,在陽臺上可俯瞰花團錦簇的巨大花園。另有一獨立階梯從廚房區延伸而出,往下通到一樓的大型水牆。有人員定期檢視,確保水質乾淨且可飲用。不幸的是,這間房子在二戰期間遭到摧毀。

開枝散葉的第二代:我的祖父尤吉尼歐(吉尼歐爺)

我的祖父吉尼歐爺和弟弟回到菲律賓後,都在田裡幫曾祖父種植甘蔗、果樹(包括:閻浮樹、四季桔和菠蘿蜜)、堅果(花生)、蔬菜(綠豆),同時也幫忙做生意。他們也幫忙看管家禽家畜,像是雞、馬和水牛。當時水牛被用來推磨,從甘蔗中擠出糖漿。他們會從清晨開始騎車巡視農地,一直巡視到傍晚。這些活動有助於他們理解中國傳統農業的整套知識,並學習如何在出口生意上應用相關的中國語言。

吉尼歐爺娶了原住民與西班牙的混血後裔,是從曼達維市來的葛瑞葛莉雅巴特倫珊帕斯。他們生了十二個小孩,六個男孩、六個女孩。他的弟弟艾斯特邦也娶了當地女子蘿莎莉雅羅德里奎茲。兩兄弟和他們的家族都繼續住在布果市。因為家族事業的關係,吉尼歐爺常往返中國,他最後一趟造訪中國則約介於1912-1914年間,當時末代皇帝還是個小男孩。

吉尼歐爺的嗜好是木工和親自監督工匠打造自己的房子。房子本身由硬木建造而成,木材包括印度紫檀、南洋櫸木和米特克斯木,依中國傳統建築建造。他甚至用塗漆的硬木(印度紫檀和南洋櫸木)來製作有扶手的椅子,放在蹲式馬桶上以方便使用。在獨立於廁所的浴室裡,有中國風的大型澡盆與水罐。為了讓我們對中國遊戲有初步認識,他製作了四張中式棋盤、兩個鑿洞的木板用來玩菲律賓播棋(一種室內遊戲,要把貝殼或石頭放進木板上的坑洞),還製作了一張專業撞球桌放在另一間房裡。小時候我看著他如何精心打磨出不同尺寸的木製「ganta」(用來估算容積的零件),只用融化的熱漿糊把木頭零件的打洞面一一黏合起來,完全不用一枚鐵釘。在二戰中,這間房子也燒毀了。但吉尼歐爺在戰後又把它重建起來。

吉尼歐爺持續種植甘蔗。在一排排的甘蔗中間,還種了花生。一旦收成,花生就會被連根拔起,作為鬆土之用,這樣就可以不需要用到水牛來鬆土。在等待甘蔗收成季節的過程中,他會在另一公頃土地上種植不同的果樹和蔬菜。收成之後,他會準備水果、醃製竹筍、乾花生、花生糖、芝麻脆糖等等,一起賣給宿霧市的中國商店。他會從中國帶回蒜頭,種植在田園裡,然後把收成的一部分送給村裡親近的中國朋友。吉尼歐爺和弟弟艾斯特邦及其他西班牙地主一起在1928創立了布果-密德林採糖有限公司(兩人都是董事會成員),主要採收離心焦糖,副產品則是糖漿。該公司外銷糖給美國。

斷不了的根:中式文化融入生活之中

除了經營家族企業和甘蔗園,吉尼歐爺在菲律賓自由邦最後的日子裡,也積極參與政治活動。作為布果市議員,他受命在距市中心相當遠的地點建設醫院。他捐出小部分沿海田地,讓病人得以呼吸新鮮空氣,並堅持在遠離人群處興建醫院,以避免傳染病的擴散。有兩次經歷強烈颱風,他提供自己的儲藏空間供難民庇護,特別是庇護小孩並提供他們食物。1949年的中國內戰後,有8名中國人來到我們村莊,吉尼歐爺幫他們建立了自己的小本生意,也和村裡其他中國社群合力創建了中文學校。1946年,吉尼歐爺被指派擔任布果市的副市長。在1946年7月4日、菲律賓允許獨立的那一刻,他和市長一同出席菲律賓獨立就職典禮,並在舊市政大樓前揮舞菲律賓國旗。

從我曾祖父那個時代到我們這一代,我的家族一直維持著中國式的傳統生活,從節日慶典到每日所食皆然。當時我們固定慶祝中國春節,有些人和其他村裡的中國家庭會一起穿著紅色的衣服。每年在宿霧市和布果市,中國人都會以遊行方式慶祝雙十節。在早餐和晚餐的選擇上,我們會吃米粥加上煎魚、炒蟹配豆豉、或配南乳(紅腐乳),中餐通常吃得比較豐盛。最受歡迎且常見食譜是:炒麵、滷肉(和乾金針、乾香菇、八角一起滷)、南乳(紅腐乳)、潤餅(只用嫩豆芽)、蛤蜊湯(不是加上麵線就是加竹蟶或炒竹蟶)、蒜炒花枝、炒雜碎和滷鴨。有時候在深夜時分,還會準備鴨羹、乾藥草根配上撈麵。然後我們也吃當地食物,像是燒肉(炸豬皮)、酸魚湯(薑味海鮮清湯)。

後記:

Marina目前在法國巴黎的國際博物館協會(ICOM)工作,與她合作完成這篇文章的日子裡,我們深切地感受到她的熱情友善,她不畏時差與工作的辛勞,及時又仔細地回覆每一封信件,並積極聯絡和家族相關的親朋好友,希望更加忠實地呈現家族移民發展的歷史。由於很多珍貴的照片與文物皆毀於二戰大火中,文章中附上的三張照片是目前倖存的珍貴襲產。此外,她還積極為我們引薦了解菲律賓華人文化襲產的人士,讓亞太博物館連線專欄有延續下去的可能。Marina特別要求我們在作者欄為她掛上家族的姓氏Yap,「我想要榮耀我的家族」(I prefer to honor my family heritage in bringing the family name Yap.)。藉著此段後記,我們想向Marina傳達感謝之意,是的,您的家族必定以您為榮。

Museum of Living Memory: The Story of a Chinese Filipino Family

Author: Marina Yap (former commissioner, ICOM) Editor: Sally, Tian Sz-Yu

My great grandfather Crisanto Yap (Lolo Santo as called by us) arrived in Bogo City, province of Cebu, Philippines, from mainland China in 1870s. It is believed that he came with his seven brothers, two of them known to our family only as Intsik Kiga and Intsik Barresto. The latter, together with Lolo Santo, settled in Bogo while a fourth brother lived in the nearby Bantayan Island. The other brothers settled in different parts of the country, but unfortunately there was no communication with each other. Lolo Santo’s family was originally from Henan but migrated to Amoy (Xiamen). When we were still young my grandfather told us that a great number of their family in China were generals of the Imperial Chinese Army.

Based on a painted portrait of my great grandfather done by one of his fellow travellers, one could see him still wearing the Changshan, a traditional Manchu style of men’s attire then imposed on all Han Chinese and worn during the Qing Dynasty. He also had a shaved forehead and the traditional long queue for the hair when he arrived in the Philippines.

As he settled in Bogo, he married Josefa Ylanan (Lola Sepa as called by us) a native Spanish mestiza. Lolo Santo had to convert to Catholicism since they were to be married according to Catholic rituals, the Philippines being then a colony of Spain. Upon conversion, he adopted the name Crisanto as his first name but kept Yap as his surname. Unfortunately no files on his full Chinese name are available since records were burned during the Second World War.

His father-in-law, Angel Ylanan served as gobernadorcillo (a municipal governor) of Bogo town from 1886-1887, and was greatly responsible for the planting and propagation of fruit trees in the area as well as the cultivation of sugarcane. In fact, the demand for muscovado sugar increased during his term.

Lolo Santo’s business, the export of copra and maguey fibers thrived and enabled him to buy land properties in the proper town in different areas in Bogo as well as 1000 hectares of farmland planted with sugar cane.

He and Josefa had five children: Eugenio (Lolo Genio), Esteban (Lolo Teban), Jacinta and Hermogina (twins) and Benedicta. My grandfather, Lolo Genio (the eldest) and Lolo Teban, his younger brother, were sent to Amoy (Xiamen) to learn Chinese languages (especially Fookien and mandarin) and Chinese culture. They stayed there for 10 years and lived with the families of my great grandfather. Separated from her two sons, my great grandmother was very sad and cried often. For her recreation and since she enjoyed gambling (like the game of hantak), Lolo Santo built a gambling den and also a big cockfighting arena in one property in the town closer to where they lived.

The house, which covers around 2,300 sq. m. was made of Spanish style, was located on a hill. Part of the hillside was flattened and the ground was levelled off and the wall of the house was constructed against the hill. The entire building, the flooring included, was made of hard woods of tindalo, narra and molave. The ground floor was used as a store and storage place for copra and maguey fibers. The first floor was four meters high from the ground floor, with at least 24 steps (broken into 6 and 18) to climb before reaching the living area with three bedrooms, the living room and the kitchen. Each bedroom covered an area of 200 square meters. The furniture was in Spanish style while the window panes were made of capiz shells. Adjacent to the living room was a door that led to a terrace overlooking a big garden full of flowers in different colors. From the kitchen area, there was a separate stairway that led down to huge covered water well on the ground floor. Someone regularly checked that the water was clean and safe for drinking. Unfortunately, this house was destroyed during the Second World War.

When my grandfather (Lolo Genio) and his brother came back to the Philippines, they both helped my great grandfather to work in the farm planted to sugar cane, fruits trees (such as lomboy, lemoncito, jackfruit), nuts (peanuts) vegetables (mongo beans) and also to take care of their business. They also took care of farm animals (chickens, horses and carabaos). The carabaos were used to turn the mills to squeeze out the molasses from the sugar cane. They rode horses to oversee the farm from early morning until late afternoon. These activities helped develop their full knowledge of Chinese traditions in farming and the use of Chinese language and writing in their export business.

Lolo Genio married a native Spanish mestiza, Gregoria Barte Lumapas from the town of Mandaue. They had twelve children, six boys and six girls. His brother, Esteban, married also a local belle, Rosalia Rodriguez. Both brothers and their families continued to live in Bogo town. Because of the family business, Lolo Genio travelled to China and the last time he visited China was sometime in 1912-1914, when the Last Emperor was still a boy.

His hobby was carpentry and administer in building his own house, which was also made of hard wood, like narra, yakal and molave according to Chinese tradition. He even used varnished hardwood (narra and yakal) to make a chair with arm rest which was placed over the squat toilet. In the bathroom, separated from the toilet room, there was a huge bathtub and a water jar with Chinese designs. To initiate us to Chinese games, he made four Chinese checker boards, two pit-carved wooden boards used for playing sungka (a parlor game which involves dropping shells or stones into large holes on the board) and a professional billiard pool placed in one room. At a young age I watched how he crafted wooden ganta (a unit to measure capacity) of different sizes using only melted hot paste to glue the joints of the perforated sides of the wood, without using nails. During the Second World War this house was burned down. But Lolo Genio rebuilt it after the war.

Lolo Genio continued to cultivate sugar cane. In between rows of sugar canes, peanuts were planted. Once matured, the peanut plants were uprooted loosening the soil. This avoided the use of carabaos. While waiting for the sugar cane harvest season, on another hectare of land he planted different fruit trees and vegetables. From the harvests, he prepared fruit and bamboo shoot preserves, which together with dried peanuts, peanut brittle, and sesame seeds brittle he supplied to Chinese shops in Cebu city. From China he brought back to Bogo some few leek green chives which he planted in his garden and he used to give some of the harvest to his close Chinese friends in the village.

Together with his brother, Esteban and other Spanish hacenderos, they pioneered the establishment of the Bogo-Medillin Sugar Milling Co. incorporated in 1928 (both were Board members) which mills centrifugal raw sugar with molasses as its by-product. It exported sugar to the U.S.

Aside from running the family business and sugar cane farm, Lolo Genio actively served the government during the last days of the Commonwealth regime in the Philippines. As a councilor of the town, he was responsible for the construction of a hospital far from the town center. He offered a small portion of his farmland overlooking the sea to provide fresh air for the patients and insisted that the hospital be built far from the population to avoid the spread of contagious diseases. Twice, during a strong typhoon, he offered his bodega (storage area) as shelter to victims especially those with children and provided food for them. After the 1949 Chinese civil war, eight Chinese arrived in our village and my grandfather helped them establish their own small business. Together with other Chinese groups in our village he helped create a Chinese school.

In 1946 Lolo Genio was appointed the municipal Vice-Mayor of Bogo. Upon the grant of independence to the Philippines in July 4, 1946, he, together with the town mayor, presided over the Philippine Independence inaugural ceremonies and raised the Philippine Flag in front of the old municipal building.

From the time of my great grandfather down to the present generation, my family kept the Chinese tradition both in the celebration of festivals and in the food we eat. The Chinese New Year was regularly celebrated, some wearing red colored clothes together with other Chinese families in the town. Each year in Cebu city and Bogo town, the Chinese celebrated the Double Ten with a parade.

For breakfast and dinner, rice porridge with fried fish or crab and black salted beans, or salted fermented red bean curd was served. Lunch was often heavy. The more popular recipes served were: chow mien, humba (with dried lily buds, dried mushrooms, gabe, 5 star anis) fermented red bean curd, fresh lumpia (strictly 3-days bean sprouts), shell soup either with misua, or razor shells or sautéed razor shells, squid with leek green chives, and chop suey and braised duck. Sometimes late in the evening he prepared tongkoi duck soup, dried herbal roots with fine noodles. Then we have native dishes like pork chicharron (deep-fried pork rind), tinola fish (a fish ginger broth).