Author: Liu Ting-Yu (Freelance writer; MA degree, Graduate School of Arts Management and Cultural Policy, National Taiwan University of Arts)

Opened to public since December 2016, AMA Museum has become a vessel, a way for contemporary society to understand the true narrative and concept of Comfort Women: female victims of violence and abuse. As a space for remembrance and reflection, the most important meaning for this museum is to identify the incidents as trauma: to establish the reality of the trauma with absolute clarity, so that the victims can truly reclaim their power, and to take back their subjectivity from secondary victimization of discrimination and defamation.

Keywords: comfort women, trauma, remembrance, subjectivity, female subjectivity

Recognition and rectification of trauma

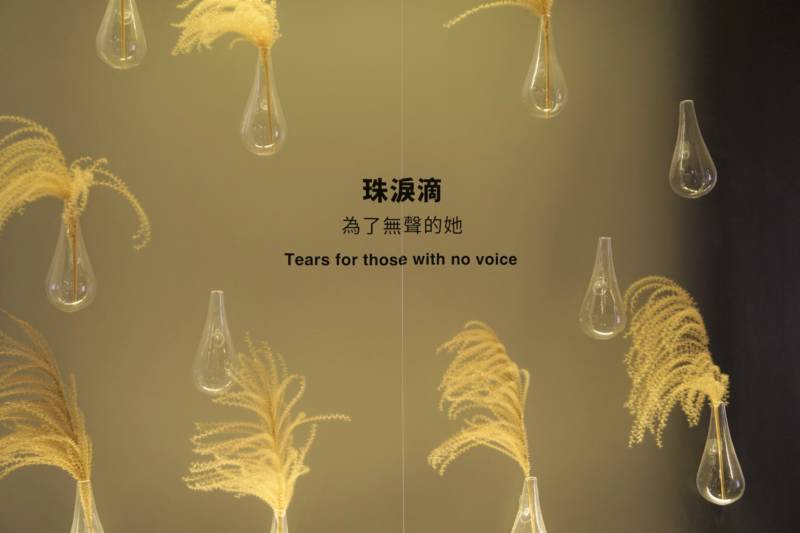

Comfort women, a term that has been repeatedly boycotted in our society, a term that has not been fully explained in text-books. What does “comfort women” really represent? What are their backgrounds and the environment they lived through? In modern society, we tend to discuss and remember the names of those who are perpetrators, but seldom remember those as victims. When we speak of Cheng Chieh (perpetrator, 2014 Taipei Metro attack), we are well aware of his background story and family; if we speak of the holocaust, we are well aware of Hitler… but in our society, the victims are usually forgotten by the public, becoming a group of people whose voice cannot be heard. When the facts cannot be revealed and the voice of the victims is buried deep under different interpretations, what do we have left apart from meaningless sorrow and hypocrisy? Where should we start to put together this section of our history, and construct the collective memories of our land?

From 1937 to 1945, the imperialist concept “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” created and promulgated by the Empire of Japan has spread all across China and South-East Asia while Japan invaded these areas. However, behind the brave military image, Japanese government established “comfort stations” in all the places they have occupied in order to prevent rape and control the spread of sexual diseases. Japan government forced women from China and South East Asia as “comfort women”, rationalizing unhuman sexual violence. In the past thirty years, through the recovering of more evidences and archival research, the stories of these “comfort women” are becoming well known by the public, encouraging people to dig deeper into the backgrounds instead of only debating if they had volunteered or not. Audiences should pay more attention to each individual. Through the understanding of each victim, it is more likely for us to feel the permanent persecution that war has caused upon each individual.

As an area to narrate the whole picture, Museums are also a place that allows the audience to simmer in history. In Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, Judith Herman (Psychiatrist, Harvard Medical School) has mentioned the importance of memorials to the victims, which can serve as a guideline to the very reason of existence of a museum in our society. When people are trying to recover from trauma, if others can not recognize their wounds as traumas, and all the symptoms – mood elevation, depression, continuous nightmare…etc, that the victim shows will only be treated as one’s over-reaction, leading to secondary injuries towards the victims. Same as the traumatized soldiers from WWI, the “comfort women” were described by our society as “moral invalids”, and people even proposed to treat these victims by humiliating, threatening and enforcing punishments. If our society cannot recognize these comfort women and the sexual violence they have been through, the public cannot understand why the symptoms such as infertility, mental illness or physical illness occurs to them. When our society cannot establish sympathy towards these women, but alienate them in our society, it only makes the comfort women more isolated for our world.

“Granny”, Shen-Jong Lin (Aboriginal name, Iyang Apay) has always been the person that brings happiness to everyone in the workshops held by Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation. Although communication is very limited due to language difference, “Granny” who loves to sing and dance can always bring joy to all the people around her. In one of the projects of the foundation, she even teased the man who received the package by joking that the package is full of US dollars, when she tried to play the role as a one-day postman. Her optimism and wisdom impress us, and is totally different from what we normally think of a traumatized person. However, if you go through the life story of “Granny”, she had four marriages, all ended by the experience she has gone through during the war – whether her husband cannot accept her once being a “comfort woman” or marital disharmony caused by the gossips of villagers. From the experiences of “Granny”, we can realize that during those times when “comfort women” were not correctly recognized by our society, and the researches still have not dug deep enough to send the right message, we know very little about how the experience can impact a victim’s life. No matter direct injuries or in-direct traumas that lead to broken families or worse relationships, the trauma only adds up one time and another till it becomes layers and layers of unbearable sorrow.

In December, 2016, AMA museum is finally opened to the public, dedicated to the comfort women during the Japanese rule in Taiwan. The museum is established to tell the stories of all these “comfort women” to the public, and hope that the society can realize the sexual violence and trauma that these people have been through, the sorrow of these comfort women can now be spread out in public. By giving recognition to the experiences of the comfort women, we hope that we can let these women realize that the pain is real and recognized by everyone else in the society. It is no longer something that you bury deep down inside your heart and doubt yourself from time to time, and finally they can accept the pain and trauma, and possibly feel that they are not isolated in our society and have brought shame upon themselves.

Historical role of AMA museum

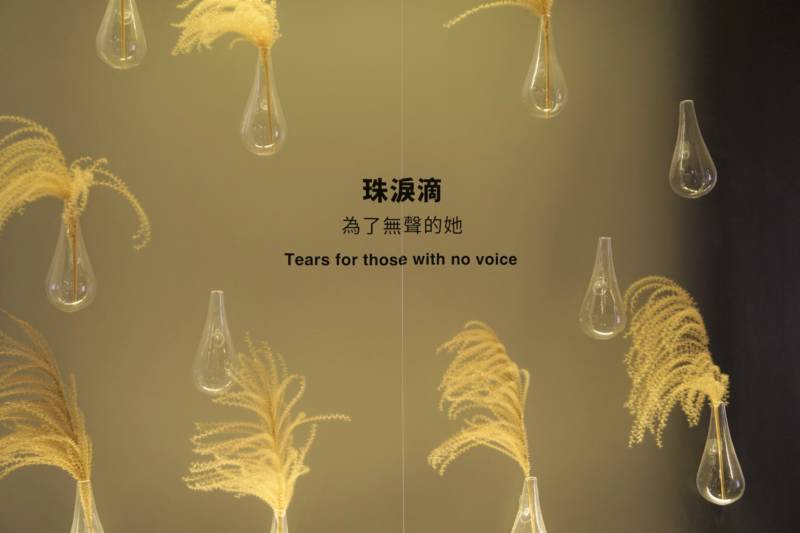

Walking into AMA museum, we can see the museum carrying out the history of the comfort women by a linear display, starting from the cause of comfort women, the background history, three different stories shared by individual, social movements, and international responses to this subject. The reeds that appear all over the museum, comes from a documentary “Song of Reeds, 2015”. Apart from traditional documentary films, “Song of Reeds” not only discussed trauma, but raised a crucial question, “How did the comfort women live their life till the end?” Audience of the film will feel deep and heart-moving to see the transition of these women from being a “victim” to a “fighter”.

From 1997, Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation has held workshops for these women for over 16 years. By means of theaters, arts, photography, the foundation allows these women to face the incident they have encountered and the source of trauma. By digging deep into the painful memories, they recognize more and realized a clearer picture of what they have been through, thus allowing them to become a fighter that understands their own rights to fight for what they deserve. This transition, once again proves the importance of rectifying, it also proves that what these “comfort women” are asking from the Japanese government is not just an apology, but also the right to feel hurt. A Korean comfort woman, Yoo Hee-nam says: “Looking back to the days we have been through, now, money is no longer an issue for us compared to back then, but what we have lost, is the right to live on as a human being; to live on a life with satisfaction.”

Professor Simine from Birkbeck College, University Of London has mentioned that over the past thirty years our society has entered an era of historical information explosion. People are willing to talk about the past, to face the oppressed, the ignored, and the persecuted and recognize the stories of these individual. Museum has become a special media in our society where we can review what war has done to our society and how we can restore social-justice. No matter serving as a bargaining counter in politics, or a memorial, museum now has its unique purpose in our lives. AMA museum is established in such times. Surprisingly, before the museum was established, there were over 60 years after the war, which Taiwan people has no recognition of these comfort women. Our society has ruthlessly ignored what have happened to these women, as if nothing has ever happened. Until 1992, former Japanese Representative Ito Hideko, confirmed the existence of Taiwanese comfort women through the archives of Ministry of Defense. From that time on, the foundation started to do researches of historical info, revealing the history of the unknown “comfort women”. The process is difficult since a lot of papers were lost, and the people are already in the elder age. It takes tremendous courage and effort for someone who hasn’t spoke of their past in 60 years to describe the trauma they have been through.

Standing at the crossroad of our era, AMA museum symbolizes the right of women. From a museum study stand point, Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation did a great job raising funds from our society and establishing this incredible place that allows the public to understand the stories of these women. The audiences come here to understand the history our land and people have been through, by embracing the stories; they further understand the vulnerability and strength of life. They relate to different aspects of the victims, no matter it is sadness, fury, happiness, or wisdom, you can all see it from the articles inside the museum. Through what they have created inside the workshop, articles, drawings, photos…etc., the victims express their true feelings. AMA museum invites everyone to come visit and know more about their stories, we can only relate by knowing more about their stories, and then unveil a part of our history. When history in more than just a page in text-books, when the stories flow through the audiences’ mind, our dark past will be enlightened, what is hard to face will no longer be that hard. Museum can bring this experience to the audiences, allowing people to broaden their minds, and create a collective memory of our society.

References:

- 楊大和(譯)(1995)。創傷與復原(原作者:J. L. Herman)。臺北市:時報文化。(原著出版年:1992)。

- 婦女救援基金會(1999)。臺灣慰安婦報告。臺北市:臺灣商務。

- Simine, S. A. (2013). Mediating Memory in the Museum. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 吳秀菁(製作人、導演)(2015)。蘆葦之歌【紀錄片】。新北市:勝琦國際多媒體公司。