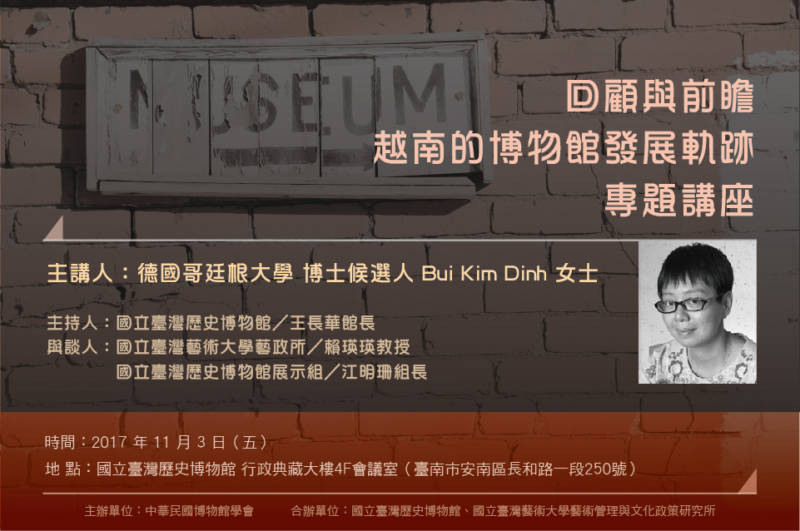

【Museums Link Asia-Pacific】Knowledge on Museum System and Other Alternatives in Vietnam -The Rise of Private Museums

Author: Bùi Kim Đĩnh (PhD candidate at Institute of Social & Cultural Anthropology of George-August University in Göttingen, Germany)

🇭🇰Vietnam Politics and Museums by Bùi Kim Đĩnh

An essay that introduces the contemporary museum development in Vietnam, and ponders on some essential museological questions.

For readers who expect museums to be more than houses of treasure display, the examples from Vietnam may provide some food for thought. We may want to ask the following questions:

Can museums ever be in the vanguard of change in its contribution to the society in transformation? How are museums political? How national political and cultural policies interact with the rise of private museums in Vietnam, and how can that be compared with what is happening in the other nations in the Asia Pacific region? What makes museums more than simply institutional entities, and what is lacking in the recent development of Vietnamese museums?

reviewed by Sun, Bai-Yi

Changes and Criticisms

Since 1997, after the success of the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology, museums have become a core factor in building a ‘new a culture with imbued national identity’ (Lê Khả Phiêu, 1998). In 2001, laws and legislation of museums were issued for the first time in the Law on Cultural Heritage. Listed are definitions, classifications, ranks, missions and rights of museums not too different from international standards. Conditions to establish a museum are promulgated for not only the state but also private ownership (Nguyễn Văn An, 2001). In 2005, a Master Plan for Developing the Museum System until 2020 was signed. The main purpose of that plan is to serve the general public needs of learning, studying, teaching, and transmitting knowledge of history, culture, sciences, and cultural enjoyment, while also contributing to the socio-economical development (Phạm Gia Khiêm, 2005). Thus, after half a century, Vietnamese museums, for the first time, are not simply considered propagandas but public services.

However, the success of this development is mostly in term of quantity. Although new perspectives, themes, and methods have been increasingly established since 1997, most of the museums in Vietnam are still far from the international museum standards. Regarding the public service, a large number of museums did not have any museum shops, cafeterias, and publications. In cases where they exist, they were usually insufficient in content. More than half of the museums have only flyers and no publication. Educational programmes appear lacking or uninviting. Usually only monotonous guided tours in museums could be offered. The majority of museum researches remained a future resource.

Reasons for this are, among other things, inadequate internal structures. Two thirds of the museums in Vietnam had no budget for educational programmes and marketing. As a result, sixty percent of the museums neither had a model or museum concept or a clear statement for their missions. Also, forty percent of the museums had no budget to preserve and expand their collection. In a collaborative programme, most museums could not afford the training cost for their employees.

Additionally, almost sixty percent of the state museums had no experts in museology such as communication, marketing, and pedagogy. This fact is caused by the lack of education in modern museology. In the whole country, there are only the Department of Cultural Heritage in the University of Culture in Hà Nội and in Hồ Chí Minh City that teach museology and heritage preservation. However, rooted in the ideologies of the Schools of Cultural Cadres in Hanoi since 1959, the Department of Museology in those universities are dominated by the doctrines of Marxist-Leninism and Hồ Chí Minh ideologies as well as the revolutionary guidance of the party. The studies of art and social sciences are also in the same situation.

Moreover, conceptualisation of a museum as a solidary process is not yet a pressing concern. In a separated administrative structure, building museums falls under the responsibilities of the Ministry or Authorities of Construction, which are usually not connected at all with museum workers, who are legitimated by Ministry or Authorities of Culture, Sport, and Tourism. An example is the new Hà Nội Museum built and designed by the architecture firm gmb Gerkan/partner GmbH [1] in 2010 and had not yet functioned because of missing exhibitions [2].

The absence of professionalism is not only a problem for museums, but also the government in Vietnam. A statistics of the number of museums in the country and their classifications could not be comprehensively listed by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Although there was a master plan for museum development until the year 2020, this plan was not based on any relevant museum research. The Yên Bái Museum is an example of a totally unsuitable development plan. The museum was built in 2009 as part of the master plan for museum development. Since then, however, it has been empty and left unfinished. Existing museum collections must be stored in rustic condition. The reason for this is the lack of subvention [3]. Hence, the master plan for museum development is not at all adapted with the local realities of museums.

Along with the quantitative boom of state museums, the number of private museums has also increased. Since 2006, there are twenty-two private museums founded, which covered almost fifteen percent of Vietnamese museums. Those museums originated from private collections and registered either as private museums or as business companies. As private museums, according to the Law on Cultural Heritage, they must be theoretically under the guidance of provincial cultural bureaus directed by provincial party committees. However, as private companies, they were authorized by Departments for Planning and Investment of provincial committees that was not at all related to cultural policies of the Party. In this sense, private museums, especially private museums registered as companies, have relatively more freedom in decision making.

Similar to state museums, the themes of private museums focus on history, anthropology, celebrities, art-antique, war, and cultural history. Almost half of them are based on collections of Vietnamese antique or modern art – mainly paintings. However, with organic staffs, private museums are more flexible and active. For example, participating in making heritage, together with the regional ethnic minorities, the Muong’s Culture Museum has organized exhibitions and workshops about traditional natural medicines from Muong’s culture. They also contribute to public education by organizing workshops about HIV prevention and educating youth about sexuality in the Muong communities. Similarly, Nguyễn Văn Huyên Museum aims to connect itself to the other cultural addresses such as temples or churches of Lai Xá village, where the museum is located. In this case, social engagement of private museums is better than state-owned ones.

Furthermore, not framed in the strict political guidance of the Party, private museums can be more open in thematizing exhibitions. Since 2011, in addition to anthropological collections about ethnic minorities, the Muong’s Culture Museum has also organized contemporary art activities such as performances, installations, talks, and exhibitions. For that, they were able to ask for fund from international organizations such as Culture Development and Exchange Fund of the Embassy of Denmark (CDEF) and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) in Vietnam.

Moreover, private museums are more dynamic in applying new media in marketing. Information package with modern layout in multiple languages is updated frequently on websites and social networks. Their cyber interaction with public is much prompter compared to state museums.

Nonetheless, private museums still share a problematic similarity with state museums: the lack of professionalism. Although some private museums declared having experts in communication, education and marketing in museums when responding to questionnaires in the survey on museum system in Vietnam 2013 by MUGOVIE, museological terms were frequently wrongly understood. In those museums, a second language never appears.

Initiated from personal hobbies and the needs of sharing self-contained collections, private museums are not obliged to open to the public. Many of them have almost no visitor services but only exhibition rooms to display their collections. Entrances are not open frequently. There is rarely a library, archive, or laboratory in such museums. Research, preservation, as well as publication are not on their interests. For most cases, these museums manage to attract only limited groups of friends or acquaintances with similar hobbies. For instance, in the case of The Private Fine Art Museum of artist Phan Thị Ngọc Mỹ, their painting collection of socialistic propaganda art during the civil war could attract only about one thousand visitor in 2013. Another case is the Museum for Revolutionary Soldiers imprisoned by the Enemies that remain unknown to the public since their operating models are based on the existence of state museums.

Furthermore, legalization for private museums in Vietnam has not included foreign ownership. It is difficult for foreigners to register their museums legally. It took years for a Japanese to operate his Wada Museum in Vietnam until he got a permit in 2012 and died soon after that because of his old age [4]. In the case of the Worldwide Arms Museum in Vũng Tàu province, it was even more disastrous. The owner of the European historical weapon collection was an English man. As a foreigner, he could not register the museum under his name, subsequently had to do it in the name of his Vietnamese wife. Because of family conflict, soon after the opening, the English man was on the verge of loosing his collection to his wife and his museum could not be operated [5].

Financial shortcomings are another common concern in running museums. Whilst there has been central budget to build a mass of state museums, there is limited budget for human resources as well as building exhibition and research. This is also not an exception for private museums. Without any public finance resource, private museums are sponsored predominantly by the owners. For the Muong’s Culture Museum, the owner, an artist, used to run a café in Hoà Bình city and sell his paintings in order to raise fund for his museum. Since 2010, the Circular Nr. 18 of the Ministry for Culture, Sport and Tourism, has allowed private museums to operate external services such as restaurant or café. Hence, the Muong’s Culture Museum could establish a museum restaurant to maintain their activities.

Unlike such private museums, private museums registered as commercial companies or as parts of commercial companies are all active. Founded on collections, which are related to the owners’ business, the museums consider visits as parts of their companies’ advertisement. In case of The Museum of Vietnamese Traditional Medicine, the founder is the owner of a pharmacy company and has done a good job in marketing the museum by cooperating with travel agents. In other cases, these museums are parts of eco-tourism companies or a resorts. Target groups of those museums are customers of their business. They usually house ethnographic collections. Characters of self-exoticism and entertainment appear more in this kind of museums.

In those museums, visitors are well cared and served as customers. They invest seriously into professional staff in fields of entertainment, communication, and marketing. They are well-connected with travel companies, agents, and magazines. Even though entrance fees are high, they attract many visitors. They cater for different groups like families, workers, officers, and travellers. However, local communities are not their target and research and sharing knowledge are not their priorities.

Regulated under commercial companionships, this kind of museums is not bound to any circulation of cultural policies. Taking it as an advantage, these museums can optimize their capacity without any obligation regarding the Law on Cultural Heritage, political guidance of the Party, as well as the limitation of bureaucracy.

Other Alternatives Open to the Public

Meanwhile, private cultural institutions initiated by individuals in different legal forms. Domdom, for example, is an experimental music group registered as a socio-political organization [6]. Sàn Art was founded in the USA as an NGO and established in Saigon. In order to mobilize and receive funding for the non-profit activities of Sàn Art, one of its founders Dinh Q. Le has negotiated with the local government to legalize a part of his organization’s activities as a registered not-for-profit business. Galerie Quynh was also registered as a shop and its collective Sao La makes up just a portion of the shop’s activities and now becomes an independent artist collective. Unlike these aforementioned groups, Nhà Sàn Collective simply runs without any legal status and DocLab goes under the umbrella of Goethe Institute.

Contributing to that scene is also a kind of café. Founded by two Vietnamese in 2012, Manzi café frequently organizes art and cultural events. Disregarding censorship, Manzi promotes contemporary arts, builds new audiences, inspires critical thinking, and nurtures a culture of debate through art exhibitions, talks, workshops, book introductions, movie screenings, music, and dance performances. Through collaborations, they work together with local artists, intellectuals, social activists, as well international cultural institutions. The space finances itself through an art shop and café/bar [7]. Not registered as a cultural institution, no official website but only facebook, Manzi has attracted a large audience to its events. It has become a well-known hub for culture and art in Hanoi.

In June 2013, a group of innovative artists founded an artistic entertainment quarter called Zone 9 in Hanoi. They have turned 1960s-brutalist Soviet-inspired pharmaceuticals factory into a chic and eclectic mix of independent cafés, vintage shops, and artists’ studios. It was a first sign of a positive modern creative industry in Vietnam. But it existed for only six months. In December 2013, Zone 9 was forced to close due to reasons of security. Since then, the space remains locked and abandoned.

The organizations and collectives above have played a critical role in public education, which is in fact a museums’ task. Ironically, supporting those activities is not the state but private sponsors and international organizations. The only concern that the state has for those happenings is censorship.

Exhibiting critical arts, which do not fit to ‘thuần phong mĩ tục’ (the pure custom and beautiful tradition) or ‘nhạy cảm’ (sensitive), are strictly prohibited. For examples, the nude performance “Fly off” by Lại Thị Diệu Hà in 2010 has led Nhà Sàn Studio to be forcefully closed until its name was changed into Nhà Sàn Collective in 2013 [8] [9]. ‘Sensitive’ issues related to political subjects are forbidden. For instance, the installation ‘the Absurd Republic’ of Trần Trọng Linh in 2012 in L’espace in Hanoi has caused the artist’s deportation at Nội Bài airport back to France although he is Vietnamese [10]. Exhibition catalogues like ‘Asian Anarchy Alliance’ sent to artist Dinh Q.Le were confiscated by the central post of Ho Chi Minh City under the label of ‘violating content’ in June 2015. Although the suppression is not as strict as in pre-1990s, tracking Vietnamese artists around the world is still an interest of Vietnamese security forces. After giving a talk about an art project during the Asia-Pacific Week in Berlin in 2015, several appointments with cultural policemen were already lined up for the artist in Vietnam upon the return.

To enforce such censorship, various departments of inner political security (such as PA83 or PA25) acting as the Party’s executive forces cooperate with cultural management institutions such as the National Post or the Ministry of Culture, Sport, and Tourism to regulate ‘an ninh văn hoá’ (cultural security) or to intervene directly by prohibiting artworks, censoring exhibitions, and even tracking wanted artists.

Beside censorship, the lack of a right to assembly, including a legal framework to establish non-governmental organizations, is another critical issue hindering the culture development in Vietnam. At the current state, it is impossible for non-governmental organizations to register as independent civil society organizations in Vietnam except as socio-political organizations under the umbrella of the Fatherland Front [11], a Party-governed body. All cultural activities and exhibitions are required to obtain license from the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism or its local level representatives, the Authority of Culture, Sport, and Tourism of the provincial People Committee [12].

In contradiction of inferior professionalism in most of Vietnamese museums, behind such cultural alternatives are individuals comprised of primarily three groups: local Vietnamese culture-makers, who developed their skills through local education and international exchange programmes or studied abroad and then returned to Vietnam; Vietnamese diasporas– ‘Việt kiều’, who emigrated to the USA and Western Europe as political refugees after 1975, and then returned to Vietnam; and international culture-makers from various national backgrounds that participate in Vietnamese society. Most of them are high qualified in their profession and well connected internationally.

However, limited by personal financial capitals and uncertain international support, activities of their organizations are not sustainable. Contrary to the inflation of state museums’ infrastructure as empty gigantic buildings with renowned designers like Hanoi Museum by Gerkan, Marg and Partner [13] and Quang Ninh Museum by Salvador Perez Aroyo [14], lacking physical spaces is a serious concern for independent and alternative spaces. Loosing the rented house, Sàn Art in Sài Gòn has shrunk to a humble library in a café and limited its activities [15]. In Hà Nội, Nhà Sàn Collective is again searching for a new donating space.

Future of Museums in Vietnam

Although movements in making culture in Vietnam have developed positively since 1998 in both state and private sectors, the lack of professional education and legal framework in culture management is impeding the museum development. Besides, censoring art and culture has pushed civil initiatives to the opposite direction with the government. Promoting nationalism and “fighting against all tendencies, which are contrary with cultural guidelines of the Party” is still the central issue of the cultural policy (Lê Khả Phiêu, 1998).

Nevertheless, since June 2014, the government has made a shift from the limiting ‘commercialized art and culture’ policy (the Party, 1991) to commercialization of art and culture through new policy in developing a ‘cultural industry’ (the Party, 2014). To provide some impetus for this new concept, in October 2014, the Goethe Institut in Hanoi hosted the seminar “Creativity and the City” with key speakers from Nhà sàn Collective and Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism. In December 2014, a Hanoi Art Market was opened officially for a month for the first time in Vietnam during high consuming season, just before Tết (Vietnamese New Year) [16].

Temporarily, rampant capitalism is another challenge to cultural development. Sniffing potential benefit of art and culture, greedy hands have just reached to the culture under the name of public service. Recently, Vincom Contemporary Art (VCCA) [17] has been opened as a gigantic contemporary art center with 4.000-square-meter within one of Vingroup shopping malls with aesthetics of Baroque and Rococo facades amongst Rome or Greece sculptures made from plaster. Arts and culture have become part of shopping and taking selfie.

Paradoxically, to redesign the city, this corporation wiped off cultural and historical relics like Ba Son harbour, which was built in 1790 by Emperor Nguyễn Ánh and became a modern shipyard in Southeast Asia in a century later [18]; and Cinematheque, an active cinema for sub-mainstream films in Hanoi founded in a colonial house in a small alley in French quarter. Backing those brutal actions is different political bodies. Cultural heritages, in these cases, are neither the state nor private concern.

Given this controversial situation among cultural policies, infrastructure conditions, legal issues and social changes, a museum as “a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates, and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment [19] for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment” seems to be still a utopia in the far future in Vietnam.

Notes:

- http://www.gmp-architekten.de/projekte/hanoi-museum.html

- http://vietnamnet.vn/vn/van-hoa/68874/bao-tang-ha-noi–khanh-thanh-roi—-dang-do.html

- http://suckhoedoisong.vn/van-hoa-the-thao/bao-tang-tien-ty-dap-chieu-co-vat-keu-cuu-20140206004924716.htm

- http://nld.com.vn/van-hoa-van-nghe/giac-mo-bao-tang-wada-dang-do-20140227222400342.htm

- http://nld.com.vn/van-hoa-van-nghe/giac-mo-bao-tang-wada-dang-do-20140227222400342.htm

- http://www.domdommusic.org/en/about-us.html

- https://www.facebook.com/manzihanoi/info

- http://en.artmediaagency.com/88936/being-an-artist-in-vietnam-interview-with-nguyen-phuong-linh/

- http://anninhthudo.vn/giai-tri/lai-thi-dieu-ha-lai-gay-soc/392585.antd

- http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam/2013/05/130508_nghe_sy_khieu_nai_toi_bo_cong_an

- http://mattran.org.vn/Home/GioithieuMT/gtc4.htm

- http://sovhttdl.hanoi.gov.vn/Pages/qnp-intro-lichsuhinhthanh-qnpstatic-12-qnpdyn-0-qnpsite-2.html

- http://www.gmp-architekten.de/projekte/hanoi-museum.html

- http://sdesign.com.vn/projects/quang-ninh-museum/

- http://san-art.org/contact/

- http://giaitri.vnexpress.net/tin-tuc/san-khau-my-thuat/my-thuat/tac-pham-nghe-thuat-duoc-mang-toi-hoi-cho-3110248.html

- http://www.vir.com.vn/vincom-centre-for-contemporary-art-opens-first-exhibition-49897.html

- http://plo.vn/bat-dong-san/di-san-sai-gon-300-nam-tu-xuong-ba-son-den-khu-cao-tang-5-ti-usd-591251.html

- http://icom.museum/the-vision/museum-definition/