【Museums Link Asia-Pacific】Knowledge on Museum System and Other Alternatives in Vietnam -Politics Dominated Museums

Author: Bùi Kim Đĩnh (PhD candidate at Institute of Social & Cultural Anthropology of George-August University in Göttingen, Germany)

🇻🇳 The past and future of public museums in Vietnam

The history of Vietnamese museums can be dated back to the French colonial rule in the early 20th century. After the communist regimes took power in 1954, the museum system in Vietnam has long been a propaganda tool to promote patriotism and national solidarity, in which the Party defined “culture” as “ideology, science and art”.

The change began in the 2000s, apart from war themes, art and cultural history content appearing more often, and many new museums were built. As public museums are the majority in the country, the government still plays a steering role to these museums. There is still a long way to go toward the diversification of museology in Vietnam.reviewed by Catherine Chen

Historical context determining Vietnamese museums

“Culture”, as the Communist Party of Vietnam (the Party) [1] defined, “includes ideology, science and art”. In the independence movement, the urgent cultural missions of Vietnamese communists were “to fight for doctrines and ideologies by defeating misleading intellectuals of Asian and European philosophies, which brought harmful effects to our country, such as: philosophies from Confucius, Mencius, Descartes, Bergson, Kant, Nietzsche, etc.” as well as “cultural schools like classicalism, romanticism, naturalism and symbolism etc.” Their aims were to build “a new socialist culture” with a “nationalistic form and neo-democratic content”. Three principles of the cultural campaign were: nationalization, popularization, and scientification. Nationalization means against all slavery and colonial influences in order to develop Vietnamese culture independently; popularization means against all policies or actions, which are not related to or opposing the masses; scientification means against all that make culture unscientific and disadvantaged. To maintain those principles, all cultural ideologies such as conservatism, eclectic, individualism, pessimism, mysticism and idealism etc. must be eradicated. Simultaneously, cultural trends that are in the Party’s favour such as Trotskyists must be prevented (Trường Chinh, 1943).

Under this guideline, after defeating the French colonialists in 1954, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam took over École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), which included Museé Louis Finot. In 1959, the Bureau of Preservation and Museums was established in this institution with a new mission of the museum “to serve the process of building and defending the country” (Hoàng Minh Giám, 1959) instead of “to offer some examples of (new) ancestors” to the colonized countries (Brusq, 2007, pp.97).

Running the war campaign, the mission of historical preservation in the North was to “fight against American Imperialism” and the “Puppet Government” of the South (Phạm Văn Đồng, 1966). In order to “deepen the hatred of the enemy, enhance the revolutionary vigilance, strengthen the will to fight against American to rescue the country and establish a socialist republic”, the museums were focused on collecting and exhibiting according to three themes: crimes of the enemy, our victories, and building the socialism. (Phan Văn Bạch, Hoàng Minh Giám, 1969). For these purposes, 14 museums were built in the North during the war and almost half of them were military museums [2]. In particular, during this time, interactive “rooms of crimes” and “hatred houses” invited the people to contribute found objects as criminal evidences of the enemy, such as blood-stained school books or the rubbles of living quarters which were bombed (Phạm Văn Bạch, Hoàng Minh Giám, 1969). These exhibiting rooms likely developed to be provincial-museums today.

After the unification with the victory of the North, the cultural policy continued to educate the public about “the love for patriotism, socialism, and national pride” and “the hatred against enemies and imperialistic Americans” in museums (Trường Chinh, 1984). Since 1975, twenty-three museums were built in a decade, mainly in the South. One third of them were again military museums. Almost forty percent were provincial museums, which were subjected to the heroic and patriotic history of the region. In addition, a large number of Hồ Chí Minh Museums were also developed. Until today, there is a Hồ Chí Minh Museums system with “fourteen museums, vestigials, and memorial sites” all over the country [3].

Despite the fact that Vietnam opened a “socialist-oriented market economy” to the world in 1986 (Võ Văn Kiệt, 1986), cultural commercialization was still prevented while private cultural activities were allowed certain degrees of freedom (the Party, 1991). Regardless of the economic crisis, thirty-three museums were still built or rebuilt without changing in communication during the next ten years.

Moreover, along with economical achievements, The 5th National Congress in 1998 had shifted the cultural policy significantly with a vibrant guideline for “an advanced Vietnamese culture with an imbued national identity” that should “promote patriotism and the tradition of national solidarity, the awareness of national independence and consolidation, and the protection of the Socialist Fatherland” (Lê Khả Phiêu, 1998). Since the 2000s, the landscape of museums has diversified in Vietnam. In roughly seventeen years, seventy-one museums were built, accounted for fifty percent of Vietnamese museums. Although the subjects of these museums were still by and large provincial histories and anthropology, art and cultural history have appeared more frequently among the war themes.

Political System

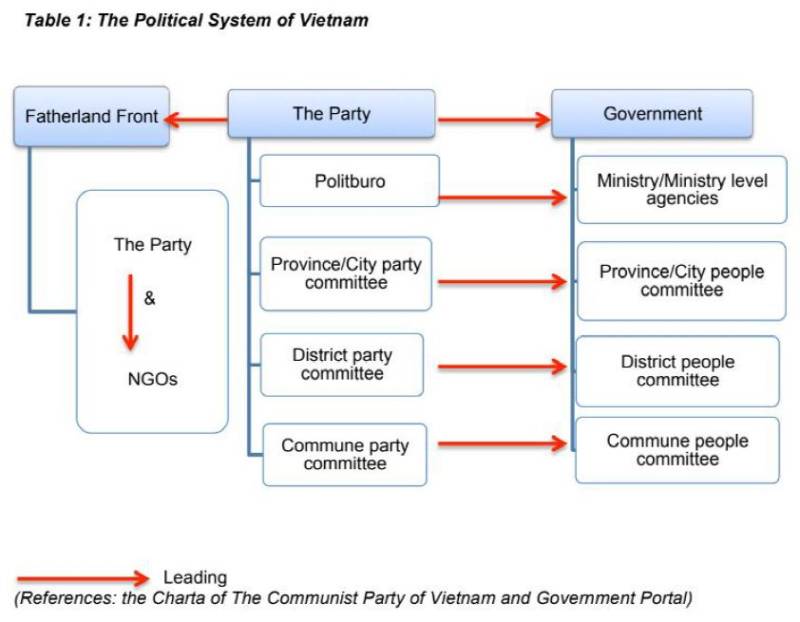

Being a political instrument, Vietnamese museums have been firmly constructed on the political system which is divided principally into three bodies: the Party, the Fatherland Front and the Government. Under those three, four administrative levels of the government are orchestrated as follow:

As above, in a one-party-system led by the Party, the Vietnamese government is constructed with four administrative divisions: central division represented by parliament, ministries, and ministry level agencies; provincial division represented by people committees of cities or provinces; district division represented by people committees of districts; and communal division represented by people committees of communes. Besides, under the commune level are resident clusters represented by collective representatives, who play a role as regulators between residents and communal governments.

Above and along this administrative system is the Party as “the leading force of the state and society” (Nguyễn Sinh Hùng, 2013). It leads the government system through the politburo and the Party committees, even has a strong hold over the Ministry of National Defences and the Ministry of Public Security. Likewise, between the Party and the government, the Fatherland Front plays a role as “a regulator” between the people and the Party-State (Nguyễn Sinh Hùng, 2013). Underneath are socio-political organizations, in which the Party is not only the leader but also one of the members [4]. Those organisations are authorized by different units of either the Government or the Party and appear as non-government-organizations in Vietnam.

To strengthen the connection between the Party and the Government, a party member network is spindled among state institutions. According to the Law for Cadres and Civil Servants, the first obligation of state officers including museum workers is to be loyal with the Party (Nguyễn Phú Trọng, 2008). They must achieve political qualifications from the elementary to the advanced levels and prove their ranking positions of institutions by declaring their loyalty to the Party (Phan Ngọc Tường, 1993). Those qualifications must be proved by state examinations (Đỗ Quang Trung, 1998).

Museum System

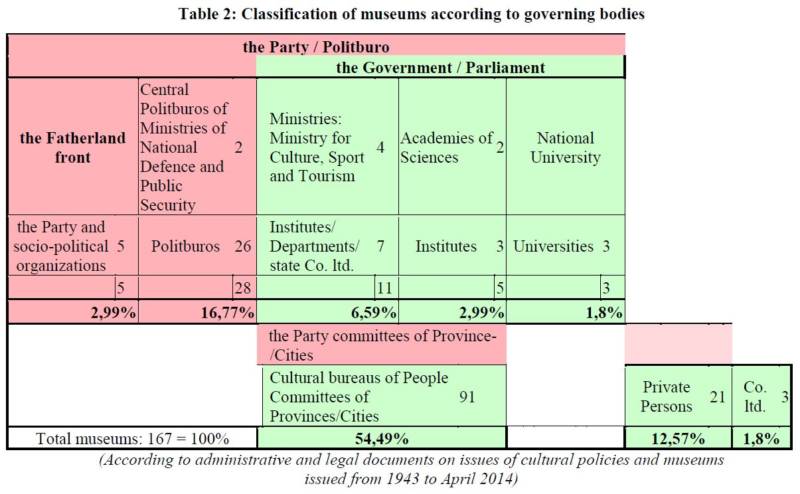

Based on this political system, the museums are orchestrated from central to local governing bodies, which are directed by either the Party or the Government. Even under different governing bodies of the Government, the Party still indirectly plays a steering role to museums.

Almost twenty percent of Vietnamese museums are under direct governance of the Party. Except some that belong to socio-political organizations, the majority is military museums and belongs to Ministry of National Defences. Only one of those goes to Ministry of Public Security. All of them are directly under the board of Politburos of those ministries.

Indirectly under the guidance of the Party’s cultural policies, most of the museums are under the management of the Government: over sixty percent belongs to the state and the majority of them are provincial museums. Amongst those, six are national museums, which were constructed by French colonialists. Meanwhile, there are only three university museums and two of them are active.

Notes:

- There is only one Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam (the Communist Party of Vietnam) that rules the state; then it is shortly officially called/written Đảng (The Party).

- The statistics in this article is resulted from the Mugovie Project and realized by the author as the M.A. dissertation Darstellung und Analyse der Museumsstruktur der Sozialistischen Republik Vietnam at the University of Applied Sciences in Berlin, 2014.

- http://www.baotanghochiminh.vn/tabid/550/default.aspx

- http://www.mattran.org.vn/Home/GioithieuMT/gtc3.htm