【亞太博物館連線專欄】政策與博物館:針對越南博物館體系與其他替代選項之理解 —政治主導博物館篇

Politics and Museums: Knowledge on Museum System and Other Alternatives in Vietnam -Politics Dominated Museums-

政策與博物館:針對越南博物館體系與其他替代選項之理解 —政治主導博物館篇

作者:Bùi Kim Đĩnh(德國哥廷根大學社會文化人類學與民族誌學系博士候選人)

編按:本文原為英文,為方便各位讀者閱讀,特由亞太博物館連線計畫團隊翻譯為中文。今年我們特別邀請作者Bùi Kim Đĩnh女士造訪臺灣,將於11月3日於國立臺灣歷史博物館(https://goo.gl/aucb4n)、11月4日於國立臺灣藝術大學藝術管理與文化政策研究所(https://goo.gl/TrZQL6)舉行座談,分享越南的博物館發展軌跡、介紹多處富含文化生命力的藝文空間。歡迎對越南或東南亞博物館感興趣的朋友共襄盛舉。

在越南,博物館的歷史起始於二十世紀初之法國殖民統治。1954年,隨著日內瓦條約簽訂,以及共產黨所領導的奠邊府大捷,越南脫離了殖民統治,卻沿著北緯17度線分為兩個國家,北越由蘇聯支持,南越則與美國關係匪淺。1975年,北越共產政權延續先前的勝利,擊敗南越統一全國。為了服務戰時體制和共產主義等意識型態,政府在全國廣設博物館體系,截至2014年止,當代越南境內已計有167間博物館之多。然而,出於越南分裂的歷史,多數1975年之前建於南越的博物館皆不為人知。本文作為柏林應用科學大學之「博物館來去越南」(Museum Goes Vietnam, Mugovie)大型企劃的一部分,希望在考慮其本身之社政脈絡下,引領讀者探討後殖民時期之越南博物館發展歷程。

一、定義越南博物館的歷史脈絡

根據越南共產黨(以下簡稱「黨」)之定義,所謂「文化」乃「包含了意識型態、科學與藝術」。在越南獨立運動期間,越南共產黨具有高度急迫性之文化任務乃「為教條與意識型態而戰,對抗諸如孔子、孟子、笛卡兒、柏格森、康德、尼采等,於我國有害之歐亞哲學思想」,另也及「包含古典主義、浪漫主義、自然主義、象徵主義等文化流派」,其目標乃是建立「一個新的社會主義者文化」,裡頭以「新民主化為體、國家主義為用」。文宣活動三準則為:國家化、人民化、科學化。國家化意指為了獨立發展越南文化,必須對抗所有的奴役與殖民影響,人民化意指反對所有與人民無關或與人民相違背的政策與行為,科學化意指反對所有讓文化不科學或淪為弱勢的政策與行為。為了推廣上述準則,所有文化意識型態,如保守主義、折衷主義、個人主義、悲觀主義、神秘主義與理想主義等皆須剷除。同一時間,黨所支持的文化潮流如托洛茨基派等則必須被留下(長征,1943)。

1954年,在擊敗了法國殖民者後,越南民主共和國政府本著上述指導原則,接收了包含路易斯菲諾博物館在內之法國遠東學院。1959年,越南政府於原址成立了文史保存暨博物館管理局,博物館任務從過往「提供被殖民者(新到來)前人的隻字片語」(Brusq, 2007, p.97),改為「為建構與捍衛國家之過程服務」(Hoàng Minh Giám, 1959)。

隨著備戰工作如火如荼,北越在保存歷史的任務上轉為對抗「美帝」以及南越的「傀儡政府」(范文同,1966)。為了「深化對敵人的仇恨,強化對革命的警醒,堅定對抗美國以拯救國家並成立社會主義共和國的決心」,博物館收藏與展出的內容均落入以下三大主題:敵人的罪行、我方的勝利、社會主義的建立(Phan Văn Bạch, Hoàng Minh Giám, 1969)。出於以上目標,戰爭期間北越一共設立了14所博物館,裡頭將近一半為軍事博物館1。特別是在這段時間裡,民眾受邀前往互動式的「罪行室」與「仇恨屋」,提供諸如沾了血的教科書、住家遭轟炸後的斷垣殘壁等,所找到能證明敵方罪行的物件(Phạm Văn Bạch, Hoàng Minh Giám, 1969),今日這些展示間多半已被改建為省立博物館。

在北越最終取得勝利並統一全國後,文化政策持續透過博物館,教育民眾有關「愛國主義、社會主義與國族驕傲的愛」,以及「對於敵人與美帝的仇恨」(長征,1984)。1975年之後的十年內,23間博物館正式落成,地點以南方為主,其中三分之一再次為軍事博物館,4成是省立博物館,教育地區內所發生的英勇事蹟與愛國歷史。除此之外,政府也開始廣設胡志明博物館,截至今日,越南各地的胡志明博物館體系計有14間博物館,以及大量的遺蹟和紀念館。2

即便越南在1986年向世界各國開放了所謂「社會主義導向的市場經濟」(武文杰,1986),文化商業化依舊不被允許,僅有私人的文化活動能享有一定程度的自由(共產黨,1991)。縱使外界面臨種種經濟危機,但在接下來的十年內,政府的文化路線維持不變,期間內修建或重建了33所博物館。

尤有甚者,伴隨著越南的經濟成長,1998年的第五屆國民議會將文化政策導向「融入國家認同後的先進越南文化」,並應「推廣愛國主義與國家團結傳統,理解國家的獨立與統一,保護社會主義祖國」等鮮明的指導原則(黎可漂,1998)。2000年後,越南的博物館領域開始出現多元化。在將近17年的時間裡,計有71所博物館落成,占越南博物館總數5成左右。縱使上述新落成博物館主題多數時候仍環繞地區歷史與人類學,但在戰爭主題外,藝術與文化史也開始頻繁出現。

二、越南的政治體系

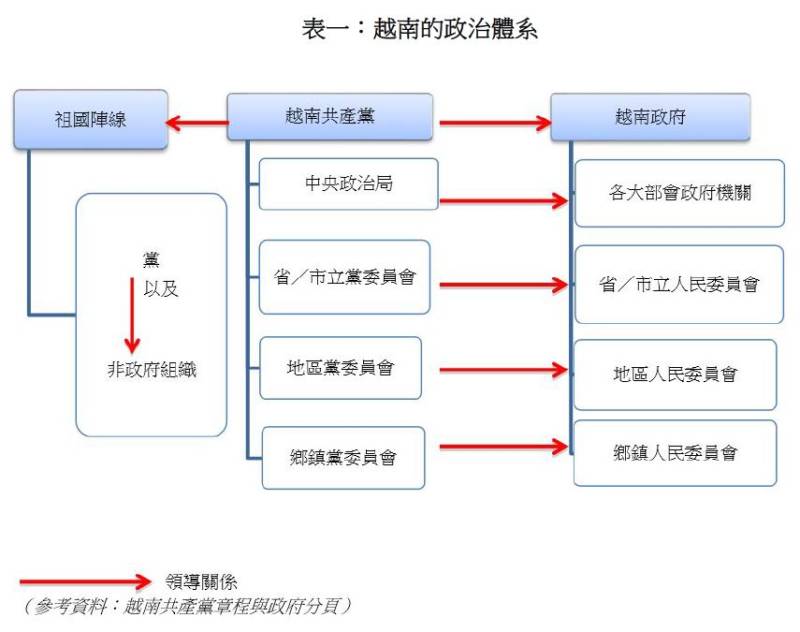

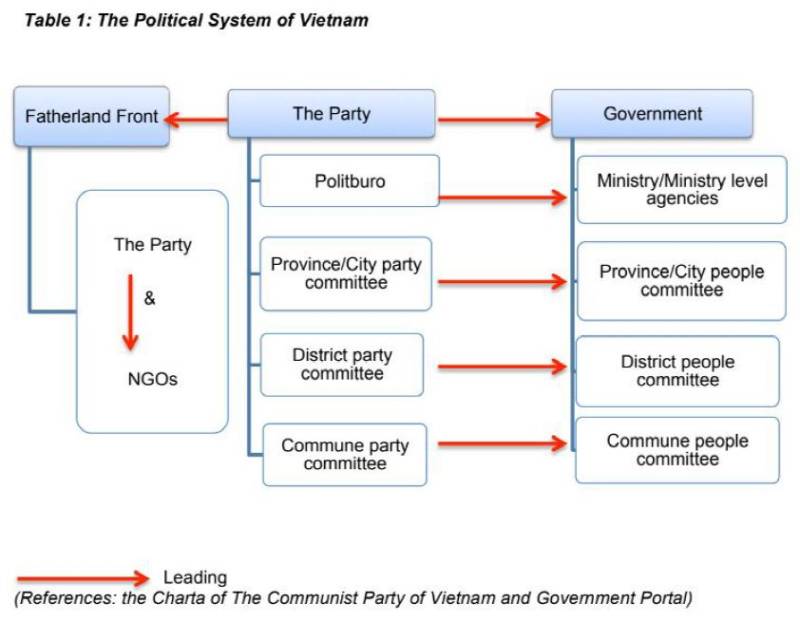

越南的博物館做為政治工具,始終緊附於政治體系之下。越南政治體系分為三大區塊,分別為越南共產黨、祖國陣線與越南政府。在三個區塊中,政府的四級行政單位建構如下:

如上圖所示,在越南共產黨所領導的一黨體系中,越南政府由四個行政級別建構而成,分別為國會與政府部會組成的中央級,直轄市或省人民委員會組成的省級,地區人民委員會組成的地方級,以及鄉鎮人民委員會組成的鄉鎮級。除此之外,鄉鎮級以下另設有集體代表所構成之住宅區單位,負責居民與鄉鎮級政府之間的調節工作。

位於行政體系之上,越南共產黨為「帶領國家與社會的力量」(阮生雄,2013),藉由政治局和黨委員會領導政府體系,同時緊握國防部與公安部。同樣的,在共產黨與政府之間,祖國陣線扮演著人民與一黨國家之間「調節者」的角色(阮生雄,2013),其下則為社政組織,必須透過不同政府或共產黨單位授權方可設立,表面上為越南之非政府組織,實際上共產黨不僅為其領導,也是裡頭成員之一。3

為了強化共產黨與政府之間的連結,各個國家機關間皆存在有共產黨的黨員網絡。根據越南幹部與公務員法,包含博物館職員在內,政府人員的第一要務便是效忠越南共產黨(阮富仲,2008)。他們必須取得基礎甚至進階的政治資格,並藉由效忠於黨確立其在單位內的領導地位(Phan Ngọc Tường, 1993)。上述資格必須藉由國家考試確認(Đỗ Quang Trung, 1998)。

三、越南的博物館體系

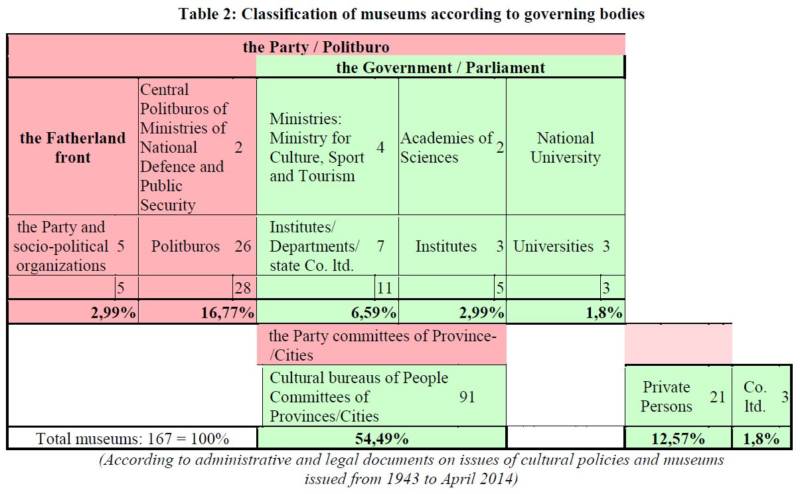

根據上述政治體系,博物館乃由中央至地方管理單位設立,後者則由共產黨或政府領導。縱使管理單位並非政府本身,共產黨仍間接控制著博物館的走向(見表二)。

接近百分之20的越南博物館乃直屬共產黨管理。除了少數歸於社政組織外,絕大多數的軍事博物館皆由國防部管理,僅有一所歸於公安部,以上全數受各別部會之政治局管轄。絕大多數博物館皆由政府管理,並間接接受共產黨之文化政策指導:逾百分之60屬於國家,其中大半為省立博物館。在這其中,6所為國立博物館,由法國殖民政府所建,但同時僅有3所大學附屬博物館,其中僅有2所仍持續運作。

Politics and Museums:

Knowledge on Museum System and Other Alternatives in Vietnam

– Politics Dominated Museums –

History of Vietnamese museums began in the early twentieth century during French colonial rule. After the Điện Biên Phủ victory under the leadership of the Communist Party and the Geneva Accords in 1954, Vietnam was liberated from colonialism but divided into two countries along the 17th parallel: the North backed by the Soviet Bloc and the South by the USA. Continuing its victory, the North defeated the South and united the country in 1975. To serve the ideology of war mechanism and communism, a museum system has been conducted and expanded in the country. Until April 2014, there had been 167 museums in modern-day Vietnamese territory. However, because of the divided history, museums built in the South before 1975 remain mostly unknown. This article forms part of the larger project “Museum Goes Vietnam” (Mugovie) at the University of Applied Sciences in Berlin and aims to illustrate how postcolonial museums in Vietnam has been developed in their own socio-political context.

1. Historical Context Determining Vietnamese Museums

“Culture”, as the Communist Party of Vietnam (the Party) defined, “includes ideology, science and art”. In the independence movement, the urgent cultural missions of Vietnamese communists were “to fight for doctrines and ideologies by defeating misleading intellectuals of Asian and European philosophies, which brought harmful effects to our country, such as: philosophies from Confucius, Mencius, Descartes, Bergson, Kant, Nietzsche, etc.” as well as “cultural schools like classicalism, romanticism, naturalism and symbolism etc.”. Their aims were to build “a new socialist culture” with a “nationalistic form and neo-democratic content”. Three principles of the cultural campaign were: nationalization, popularization, and scientification. Nationalization means against all slavery and colonial influences in order to develop Vietnamese culture independently; popularization means against all policies or actions, which are not related to or opposing the masses; scientification means against all that make culture unscientific and disadvantaged. To maintain those principles, all cultural ideologies such as conservatism, eclectic, individualism, pessimism, mysticism and idealism etc. must be eradicated. Simultaneously, cultural trends that are in the Party’s favour such as Trotskyists must be prevented (Trường Chinh, 1943).

Under this guideline, after defeating the French colonialists in 1954, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam took over École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), which included Museé Louis Finot. In 1959, the Bureau of Preservation and Museums was established in this institution with a new mission of the museum “to serve the process of building and defending the country” (Hoàng Minh Giám, 1959) instead of “to offer some examples of (new) ancestors” to the colonized countries (Brusq, 2007, pp.97).

Running the war campaign, the mission of historical preservation in the North was to “fight against American Imperialism” and the “Puppet Government” of the South (Phạm Văn Đồng, 1966). In order to “deepen the hatred of the enemy, enhance the revolutionary vigilance, strengthen the will to fight against American to rescue the country and establish a socialist republic”, the museums were focused on collecting and exhibiting according to three themes: crimes of the enemy, our victories, and building the socialism. (Phan Văn Bạch, Hoàng Minh Giám, 1969). For these purposes, 14 museums were built in the North during the war and almost half of them were military museums. In particular, during this time, interactive “rooms of crimes” and “hatred houses” invited the people to contribute found objects as criminal evidences of the enemy, such as blood-stained school books or the rubbles of living quarters which were bombed (Phạm Văn Bạch, Hoàng Minh Giám, 1969). These exhibiting rooms likely developed to be provincial-museums today.

After the unification with the victory of the North, the cultural policy continued to educate the public about “the love for patriotism, socialism, and national pride” and “the hatred against enemies and imperialistic Americans” in museums (Trường Chinh, 1984). Since 1975, twenty-three museums were built in a decade, mainly in the South. One third of them were again military museums. Almost forty percent were provincial museums, which were subjected to the heroic and patriotic history of the region. In addition, a large number of Hồ Chí Minh Museums were also developed. Until today, there is a Hồ Chí Minh Museums system with “fourteen museums, vestigials, and memorial sites” all over the country.

Despite the fact that Vietnam opened a “socialist-oriented market economy” to the world in 1986 (Võ Văn Kiệt, 1986), cultural commercialization was still prevented while private cultural activities were allowed certain degrees of freedom (the Party, 1991). Regardless of the economic crisis, thirty-three museums were still built or rebuilt without changing in communication during the next ten years.

Moreover, along with economical achievements, The 5th National Congress in 1998 had shifted the cultural policy significantly with a vibrant guideline for “an advanced Vietnamese culture with an imbued national identity” that should “promote patriotism and the tradition of national solidarity, the awareness of national independence and consolidation, and the protection of the Socialist Fatherland” (Lê Khả Phiêu, 1998). Since the 2000s, the landscape of museums has diversified in Vietnam. In roughly seventeen years, seventy-one museums were built, accounted for fifty percent of Vietnamese museums. Although the subjects of these museums were still by and large provincial histories and anthropology, art and cultural history have appeared more frequently among the war themes.

2. Political System

Being a political instrument, Vietnamese museums have been firmly constructed on the political system which is divided principally into three bodies: the Party, the Fatherland Front and the Government. Under those three, four administrative levels of the government are orchestrated as follow:

As above, in a one-party-system led by the Party, the Vietnamese government is constructed with four administrative divisions: central division represented by parliament, ministries, and ministry level agencies; provincial division represented by people committees of cities or provinces; district division represented by people committees of districts; and communal division represented by people committees of communes. Besides, under the commune level are resident clusters represented by collective representatives, who play a role as regulators between residents and communal governments.

Above and along this administrative system is the Party as “the leading force of the state and society” (Nguyễn Sinh Hùng, 2013). It leads the government system through the politburo and the Party committees, even has a strong hold over the Ministry of National Defences and the Ministry of Public Security. Likewise, between the Party and the government, the Fatherland Front plays a role as “a regulator” between the people and the Party-State (Nguyễn Sinh Hùng, 2013). Underneath are socio-political organizations, in which the Party is not only the leader but also one of the members. Those organisations are authorized by different units of either the Government or the Party and appear as non-government-organizations in Vietnam.

To strengthen the connection between the Party and the Government, a party member network is spindled among state institutions. According to the Law for Cadres and Civil Servants, the first obligation of state officers including museum workers is to be loyal with the Party (Nguyễn Phú Trọng, 2008). They must achieve political qualifications from the elementary to the advanced levels and prove their ranking positions of institutions by declaring their loyalty to the Party (Phan Ngọc Tường, 1993). Those qualifications must be proved by state examinations (Đỗ Quang Trung, 1998).

3. Museum System

Based on this political system, the museums are orchestrated from central to local governing bodies, which are directed by either the Party or the Government. Even under different governing bodies of the Government, the Party still indirectly plays a steering role to museums (See Table 2).

Almost twenty percent of Vietnamese museums are under direct governance of the Party. Except some that belong to socio-political organizations, the majority is military museums and belongs to Ministry of National Defences. Only one of those goes to Ministry of Public Security. All of them are directly under the board of Politburos of those ministries.

Indirectly under the guidance of the Party’s cultural policies, most of the museums are under the management of the Government: over sixty percent belongs to the state and the majority of them are provincial museums. Amongst those, six are national museums, which were constructed by French colonialists. Meanwhile, there are only three university museums and two of them are active.

注釋

- 本文所引用之數據來自Mugovie企劃,並於作者本身柏林應用科技大學2014年碩士論文「Darstellung und Analyse der Museumsstruktur der Sozialistischen Republik Vietnam」裡加以統整。

- http://www.baotanghochiminh.vn/tabid/550/default.aspx

- http://www.mattran.org.vn/Home/GioithieuMT/gtc3.htm