【Museums Link Asia-Pacific】Contemporary Māori Art: The Conversation between Urban Māori Identity and Art-Making Process

Robert Jahnke, KAOKAO, 2017, powder-coated stainless steel; mirror; neon, © LUX Light Festival.

Author: Ting-Ya Chuang (MA, Art Museum and Gallery Studies, University of Leicester)

When the tribal identity was deconstructed and relocated in urban social setting during the 1960s in New Zealand, the discourse and narrative of Māori identity have since then shifted and developed into a modern conception with diverse representation. Contemporary Māori art within the changing attitude of identity emerged in the early year of Māori urbanisation. The formation of this new art practice has adapted western art materials and skills to articulate Māori stories. However, the social structure experienced a radical transformation after the Māori renaissance movement, which fundamentally reconstructed the representation of Māori art. From the perspective of contemporary Māori art, this article devotes attention to the representation and construction of urban Māori identity. It explores how contemporary Māori artists negotiate the gap between contemporary Māori life in the New Zealand society and its representation in museums and galleries.

Keywords: contemporary Māori art, Māori artist, urban Māori identity, self-identification, Indigenous art

With regard to the definition of Māori artist, this article considers the artists with Māori ethnicity. Specifically, there are Māori artists who self-identify their cultural identity as Māori, whereas some Māori artists who claimed to be considered simply as artists without any reference to race. Nevertheless, the contributions and impacts from both perceptions are all significant within the development of contemporary Māori art.

Contemporary urban Māori identity as a dynamic pattern

Urban Māori living has developed into a new phase with young generations born and raised in the city environment. Whether one would define the social context is now bicultural or multicultural, it undoubtedly manifests a dynamic urban living with regard to the different cultural characteristics and the socio-economic realities. The process of defining and reshaping urban Indigenous identity essentially illustrates the interrelationship between the dynamic social context and the complex structure of Māori culture. To give an in-depth discussion of urban Māori diversity, apart from the contemporary social setting, Māoritanga (all things Māori or Māori culture) is also a significant aspect needed to be considered. Even though urban Māori is now accommodating with new associated communities and institutions, such as churches, sport clubs and urban marae (a ceremonial meeting ground), the traditional tribal-based structure has still been the core of an independent variable for building contemporary Māori identity since the postwar drift (Papesch, 2015; Paringatai, 2014; Walker, 1979). Based on whakapapa (genealogy), which ties individuals to a wider collective kinship relation, the iwi (a tribe or a confederation of clans) identification specifically accentuates the internally diversity of Māori. The traditional social units – whānau (family), hapū (sub-tribe or extended family group) and iwi – with the shared values, experiences, and belief systems, present the intricate boundaries of the collective identity. From Māori perception, mātauranga (knowledge), which attests Māori indigeneity, and distinguishes different iwi apart from one another, is inherited through different mediums such te reo Māori (the Māori language), whakairo (in modern usage refers to wood carving) and tā moko (traditional Māori tattoo) within each social group. As Walker observed, ‘the distinction of indigeneity is highlighted when a Māori person introduces themselves to another Māori, expressing who they are and from where they descend’ (2019, p.4).

In the modern society, it is inevitable that most of the urban-based Māori are alienated from their ancestral environments. The collective iwi identity apparently becomes the acquired knowledge that Māori people need to learn and reclaim in the urban iwi groups by the individuals (Walker, 2019). Additionally, various statuses of lifestyle, the socio-economic difference, and different levels of accommodating to the urban milieu all appear to complicate the contemporary urban Māori identity (Kukutai, 2011). In recent years, much research applies these two salient variables – the traditional Māori social network and urban living reality – as the central dimensions to categorise urban Māori identity (Houkamau and Sibley, 2015; Kukutai, 2011; Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa, 2019; Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa, 2020). Both qualitative and quantitative research reveal that a genuine Māori model certainly cannot serve the diverse representation of contemporary urban Māori. Significantly, the results implicate the struggles between an individual and the collective in the journey of self-determination. To identify this diversity, Durie (1994) proposed with three possible sub-groups: the ‘culturally’ Māori who understand their Māori whakapapa, use te reo Māori as their first language, and are familiar with tikanga Māori (Māori customary practice); the ‘bicultural’ Māori who evaluate their Māori identity positively and can accommodate effectively in a Pākehā (person of European descent) cultural context; and a ‘marginalised’ group which cannot relate to Māori or Pākehā effectively. A similar division was suggested by Williams (2000, cited in Houkamau and Sibley, 2015) who proposed an additional sub-group. As he noted, Māori in this group are socially and culturally indistinguishable from Pākehā. In other words, although members of this group are ethnically Māori, being simply a Kiwi or New Zealander is the finest representation of their self-identification.

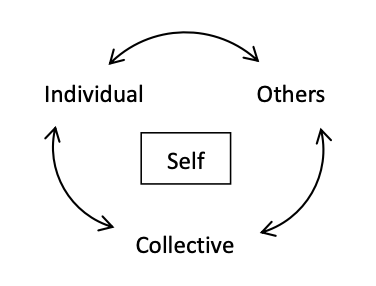

Furthermore, what Papesch stated underpins the importance of cultural practice and institutions that are now the foundation for the young generations to utilise and activate Māori identity. Specifically, through the lens of Māori perspective, discourse and narrative upon the construction of urban identity not only probe the formation of collective identity but also reveal the composition of self-identification from the urban-based individual’s experiences. Thus, in order to explore the diverse pattern of urban Māori identity, it requires different approaches rather than using one single ethnic scope. The discussion of urban Māori identity then can be understood as a structure with the interrelated segments of individual (Māori non-Māori), collective (the general society and Māori communities), and others (groups and institutions), which all related to the construction of self-identification in the shared urban social space (Figure 1). As shown in this structure, itgives an overview of the configuration and relationships in which the internal factor could relate to each of the circulated environment. An urban-based Māori self-identification in this structure entangles with the continuous dialogues and interactions with people, societies and communities which are formed by Māori and non-Māori bicultural context in the urban spaces. The self is an individual and can be in different groups in the social spaces. It is particularly the urbanisation that enhances the voice of self in the contemporary time.

Looking back to step forward

Like most urban-based Māori people who obtain their mātauranga Māori through a series of self-identification process with different individuals, collectives and communities. Similarly, in art world, many contemporary Māori artists in the position of self (see Figure 1) interact with diverse art institutions, Māori and non-Māori audiences, international forums, and particularly important, with artists themselves. The complexity and diversity of Māori art from the art-making process, or more likely as Fred Myers (2002, p.351) suggested, the process of ‘culture making’ which remains the agency and creativity of artists themselves, would then be effaced. Indeed, there are Māori artists who claim to have their artworks read without Māori reference as Ralph Hōtere declared in 1976: ‘I am Maori by birth and upbringing. As far as my work is concerned this is coincidental’ (Davis, 1976, p.29, quoted in Mane-Wheoki, 2014). Whereas some artists fundamentally seek the connections of Māoritanga and Māori community by employing specific approaches such as certain materials or motifs into their artworks. Perhaps even in this contemporary moment, the relationship between customary and contemporary Māori art remains unclear, and is still held in tension that one would experience from some of the artworks and arranged art spaces. Though neither statement denies the other, these difficult issues within Māori art however seem only to be constrained in the binary framework. Certainly, one should not expect only one perception from an artwork or a category of art. Thus, this could explain Hōtere’s remarkable influence in contemporary Māori art as his work was presented differently in both Māori and non-Māori art exhibitions.

Rather than focusing on the presented outcome of an artwork, the discussion emphasises the process of constructing, interpreting and negotiating that can provide diverse discourse of Māori art and urban identity.

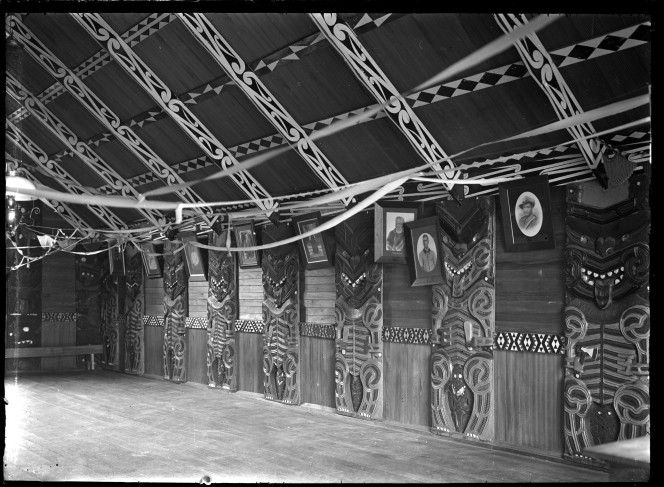

An expanded dialogue of Māori identity was created by the renowned Māori artist Lisa Reihana, who is a multi-disciplinary artist of Māori and Pākehā descent. Her contemporary artwork Digital marae (Figure 2, 3) at first glance might be an idea redefining the traditional meeting place. Rather, it significantly challenges the way people negotiating the representation of the past and the present. The core value of marae and wharenui (meeting house) is in fact retained in the gallery space. Marae is the place for gathering people, meeting people, and respecting each other. As a forum for everyone, people have the same right to discuss and debate – men and women, elder and youth, Māori and non-Māori. With this regard, Reihana welcomes visitors to walk into the virtual wharenui, and be in the dialogue of contemporary urban Māori and the wider Māori spirit. The response to Māori identity then becomes a conversation rather than a narrative. These life-size photographs attached with strong modern sense portray the Māori ancestral figures which represent the complexity of Māori mythology from traditional marae (Figure 4) (Devenport, n.d.). Moreover, Digital marae demonstrates the power of image-making, since each image can be displayed as an individual portrait, while together these images build a sacred space as an architecture of whakapapa and grow into the tacit sculptures. Thus, Reihana has pushed the boundary of urban Māori identity into a wider consideration to reach the broader audience. Notably, Reihana sees herself as a carver in Digital marae through the implementation of the contemporary art framework, since the making of marae wooden carving is traditionally undertaken by men. However, the marae is not transformed here, that it is more for the utilisation of contemporary and tradition (Thomas, 2017). The discourse of Māori identity from Digital marae, which represents the evolving nature of contemporary Māori art, tends to be reconceptualised as the inspiration of living reality (Cull, 2017).

Cosmopolitan identity?

Contemporary Māori artist Brett Graham asked: ‘Do galleries bring the young ones [artists] in because our work is comfortable, safe and non-challenging, or is it that they’re truly concerned with biculturalism?’ (1995, p. 17, quoted in Rennie, 2001, p.28). The conversation of customary and contemporary Māori art has changed. Contemporary Māori art today seems more accessible in Aotearoa (in modern usage refers to New Zealand), and has become cosmopolitan. Yet it frequently deals with issues that could always be related to the contemporary urban Māori reality. This land is my land; this land is your land (Figure 5) from the leading Māori artist Robert (Bob) Jahnke highlights the artist’s self-identification and, more precisely, the narrative of urban Māori identity. This work, referencing the famous Victory over death 2 by the Pākehā artist Colin McCahon, incorporates the Māori term wai (water) and the place Waipiro Bay where Jahnke’s ancestral marae is located (Amery, 2013). As an educator and a Māori artist, Jahnke reveals his construction of identity through the ongoing exploration in the art-making process. However for Jahnke, Māori always comes first as the given pathway towards the wider interpretation (Amery, 2019). It could be seen as a strong support for the statement from This land is my land; this land is your land, that the tribal identity and the contemporary New Zealand identity thus are not antithetical. KAOKAO (Figure 6) is another response from Jahnke who manifests the interplay between the past and the present. The double-x forms the tukutuku pattern (the chevron and latticed pattern inside wharenui) and the signatures from the treaty document. In the dark, the repetitive neon pattern lights infinitely and gradually disappear into the darkness (Figure 7). Yet during daytime, this installation reflects the real world from where it stands (Figure 8). It is specifically in the urban milieu that KAOKAOenables people to mirror the personal stories and the collective memories while acknowledging the significance of the historical aspect in the contemporary living reality of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Conclusion

In response to the living realities of urban Māori life, contemporary Māori artists, who apply different connections to engage with the past and the present, has demonstrated the significance of working with the Māori community in the art-making process. As an artwork can be seen as the negotiation and interaction between the artists themselves and the different collectives, these artists reveal their personal connections to the people, the land and the history through the construction of self in the art-making process. Consequently, the essence of being Māori enables art to facilitate the various voices from the Māori community while reaching to the wider context. As McCarthy said, ‘let the community speaks for itself’ (2020). The diversity of the representation in urban Māori identity will then come across.

Bibliography

- Amery, M. (2013) ‘On Song’, The Big Idea, Available at: https://www.thebigidea.nz/news/columns/mark-amery-visual-arts/2013/nov/136573-on-song

- Amery, M. (2019) ‘Things I learned at art school: Bob Jahnke’, The Spinoff, Available at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/art/03-10-2019/things-i-learned-at-art-school-bob-jahnke/

- Cull, C. (2017) ‘Lisa Reihana: A continuum of Māori practice’. in Whaanga, H., Keegan, T.T. and Apperley, M. (eds.) He Whare Hangarau Māori: Language, culture & technology. pp. 200-210.

- Devenport, R. (n.d.) ‘Digital Marae‘. Available at: https://govettbrewster.com/collection/2008-5

- Durie, M. (1994) Whaiora: Maori health development. Auckland, N.Z.: Oxford University Press.

- Houkamau, C. and Sibley, C. (2015) ‘The revised multidimensional model of Māori identity and cultural engagement (MMM-ICE2)’, Social Indicators Research, 122(1), pp. 279-296.

- Kukutai, T. (2011) ‘Maori demography in Aotearoa New Zealand: Fifty years on’, New Zealand Population Review, 37, pp. 45-64.

- Mane-Wheoki, J. (2014) ‘Contemporary Māori art – ngā toi hōu – Te toi hou a te Māori, te toi taketake a te Māori‘. Available at: https://teara.govt.nz/en/contemporary-maori-art-nga-toi-hou/page-2#1

- McCarthy, C. (2020) Skype interview with Ting-Ya, C., 11 June 2020.

- Myers, F. R. (2002) Painting culture: The making of an aboriginal high art. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Papesch, T. R. (2015) Creating a modern Maori identity through Kapa Haka. University of Canterbury.

- Paringatai, K. (2014) ‘Māori identity development outside of tribal environments’, Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 26(1), pp. 47-54.

- Rennie, K. (2001) Urban Maori art: The third generation of contemporary Maori artists – Identity and identification. Master of Arts in Art History, University of Canterbury.

- Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa (2019) ‘2018 Census’, Available at: http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/index.aspx?_ga=2.151739641.155575709.1592698207-157805169.1587307469

- Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa (2020) ‘Te Kupenga: 2018 (provisional) – English: Māori wellbeing‘. Available at: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/te-kupenga-2018-provisional-english

- Thomas, N. (2017) ‘Lisa Reihana: Encounters in Oceania’, Artlink. (Issue 37:2).

- Walker, D. (2019) ‘What is indigeneity?’, Te Kaharoa, 12(1), pp. 1-12.

- Walker, R. (1979) ‘The Maori in the future: A woman’s view’. in New Zealand Planning Council (ed.) He Matapuna: A source, some Maori perspectives. Wellington.