【Museums Link Asia-Pacific】The Tài Tử Music and the Người Chăm Dancing: Intangible Cultural Heritages of Vietnam

Author: Yuan, Hsu-Wen (Curator & Research assistant, Education Department, National Taiwan Museum)

As the only socialist country in Southeast Asia, the preservation of intangible cultural heritages in Vietnam plays a crucial role in the promotion strategy towards the image of the country in the global community. Vietnam thus can participate in international dialogues with more cultural elements, and let the world see various and abundant cultural heritages of Vietnam. Vietnam, which officially has 54 ethnic minorities and uses intangible cultural heritages as a means of diplomacy and tourism, still has some historical roots and backgrounds that cannot be easily understood and imagined by the outside world. As a member of the global Islamic community, the Người Chăm has a very unique identity in Vietnam. Vietnam government directly controls whether the traditional dances and musical instruments of the Người Chăm could perform outside of the country. Therefore, the Người Chăm performances in the show are reinterpreted by the Viet. Similar to the concepts that Taiwanese Han people explain the culture of the indigenous people. This article will discuss the Tài Tử Music and the Người Chăm Dancing performing in National Taiwan Museum, and explain the mutual interpretation and understanding between the performers and viewers, as well as the arouse of hometown memories of Vietnamese immigrants in Taiwan.

Vietnam, lying south of China and east of Cambodia and Laos, has over 95 million people and ranks as the 15th populated country in the world. The capital of Vietnam is Hanoi and the largest city is Ho Chi Minh City which was once called Saigon before. At present time, Vietnam has 54 ethnic minorities and the biggest one of them is Người Kinh, also known as Người Việt, which is the main ethnic community in the country.

Traditional Vietnamese dancing in Taiwan

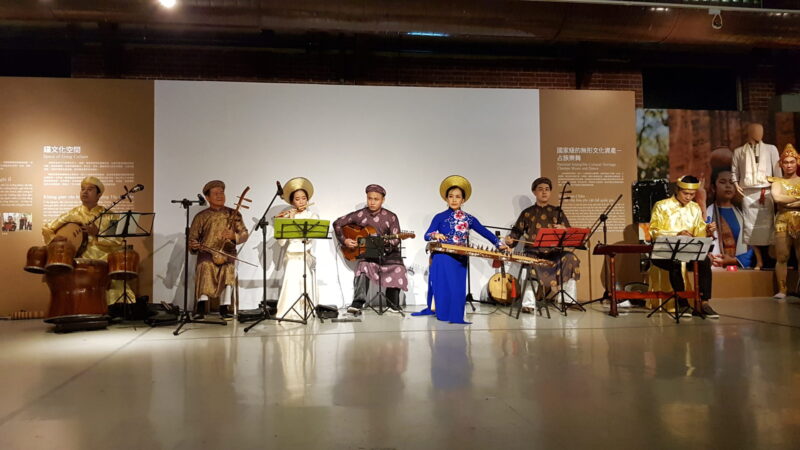

TNUA Department of Traditional Music, School of Dance, The Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Department of Traditional Music and Department of Dancing in The Conservatory of Ho Chi Minh City co-organized the event “Stunning Vietnam- 2019 International Exchange for Intangible Cultural Heritages in Vietnam”. The students from the Conservatory of Ho Chi Minh City would have a little tour in Taipei after the show; therefore, National Taiwan Museum invited them to participate the event on the first floor. They performed 9 songs, including Người Chăm party songs, Người Chăm Apsara, songs of the Huế Royal House, the Tài Tử Music from southern Vietnam and songs describing folktales and love stories reflecting the diversity of ethnicities.

Developed in the late 19th and early 20th century, Tài Tử is a famous traditional music in Vietnam which were entertainment after work, reflecting the emotion and living condition vicariously. The band played Vietnamese Guzheng, Erhu, monochord, Đàn nguyệt and traditional cajon; also, the Người Chăm dancings were presented in this event.

Ancient and mystical Người Chăm dancing

Người Chăm (also named as Chăm Pa) was a strong and promising kingdom, established in the 2nd century AD on the mid-coast of present Vietnam. The country acquired massive territories from the mid-Vietnam to the eastern part of present Cambodia. Người Chăm sailed to the present Vietnam through maritime trades and occupied the seaside areas at the middle area of Vietnam; meanwhile, it interacted frequently with the royal houses and civilians of Malaysia, Philippines and the Indonesian ancient country of Majapahit.

Người Chăm is one of the largest 14 groups out of 54 ethnic minorities in Vietnam. The Cham language originated from the Austronesian languages. Người Chăm was once all Hindus, part Buddhists later and mostly Muslims now. The Người Chăm dancings were a part of rituals, a necessary link to worship the gods; among them, Apsara is derived from walls of Hindu temples in My Son Sanctuary (Thánh địa Mỹ Sơn) at central Vietnam. Aspara focuses on the dynamic presentation of dance; while the “Fan Dance” is famous for imitating all kinds of birds. For the audiences, the ancient and mystical Người Chăm dancings are easily mistaken as dancing from Angkor Wat, India and Middle East; therefore, I would like to remind the readers of the fact that The Người Chăm are a different group from Khmer people, whose language is from Austroasiatic languages. However, due to the geographical location, the influence of Hindu beliefs and Islamic clothing features still remains. Placed on the buildings in Angkor Wat, god statues of Siva, GAṆEŚA, NAGA (or named as the dragon king, representing abundant water) and GARUDA (the vehicle mount of Hindu god VIṢṆU) etc. can also be seen at the historical sites of Người Chăm in My Son Sanctuary. As audiences of this cultural event, we should do more researches and make discussions directly with the people carrying on the culture of Người Chăm.

Absurdity and nostalgia: traditional dancing in Vietnamese hearts

The performance has also drawn a lot of attentions amongst overseas Vietnamese scholars and they have informed us privately that it is “absurd” and upset to see the combination of Người Chăm music played by Tài Tử bands, since the two are completely different performance types. Going through history, the ancient and strong Người Chăm had fought against the Vietnamese kingdom frequently in history, and the border had been often changed because of battlefield situations. The Viet, coming from the north and influenced by Chinese culture had been combating continuously and contradictorily in various relationships between dominance and subordination with Người Chăm immersed by Hinduism and Islam. In 17th century, the Người Chăm were defeated by the Viet and kept arousing random resistance to Vietnam government. Eventually, the maritime empire became an ethnic minority in Vietnam.

Nowadays, under the policy of Vietnam, Người Chăm with the identity of an ethnic minority, are not allowed to perform abroad without permission of the government. Also, My Son Sanctuary has become a reserved site for tourists and the Người Chăm dancings are no longer the same as before. In order to have the Người Chăm dancings presented in Taiwan, TNUA Dept. of Traditional Music had tried its best to negotiate and strive for this opportunity. Even though the way of performance was considered ridiculous by Vietnamese scholars, for the Conservatory of Ho Chi Minh City and TNUA Dept. of Traditional Music, to be able to present the traditional dancing of the Người Chăm culture is still a great achievement to promote and preserve the cultures of ethnic minorities.

In this event, we had many new immigrants from Vietnam and Indonesia to watch the performance in the National Taiwan Museum. One of the new immigrants from the southern Vietnam who grew up with the Tài Tử music immediately told me that she misses her hometown and mother with tears in her eyes. And those from northern Vietnam told me that these performances were exactly the same as they watched in their hometown after the show. The performers and immigrants all had a great afternoon. Since the performers were going back to Vietnam the next day, one of the museum new immigrant ambassadors from Vietnam, she led them to visit the city and had a great time in Taiwan. From the effort and insistence of the schools of Ho Chi Minh City Musical School and National Taipei University of Arts, we had the chance to see experience the richness and diversity of Vietnamese minority cultures once again.

Epilogue:

From 1960 to 1973, the Vietnamese population and natural environment were tremendously destroyed by bombs and Agent Orange in Vietnam War (Vietnamese call it “American War"), causing severe casualties. On April 30, 1975, North and South Vietnam reunified (as well as known of the Fall of Saigon, from the perspective of Southern Vietnamese), many Chinese Vietnamese and locals became refugees (or known as “Boat refugees" and “Thuyền nhân Việt Nam" in Vietnamese), separating in the areas in America, Canada, Europe, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, etc. I had gotten on the bandwagon to celebrate “Reunification Day" on social media and immediately received a private message from a Vietnamese elder living in Canada, asking me seriously to remove the relative remarks, articles, and sentences. That is the moment that I have realized that for those Vietnamese who turned into refugees at those times, it was an unforgettable day that tore them apart and made them go far away from home.

Since the 1990s, Vietnam has become a promising country attracting many Taiwanese enterprises because of the enormous population and cheap labor force. Meanwhile, plenty of Vietnamese women come to Taiwan for marriage, changing the population structure, culture, and society ethnicity. However, the Taiwanese have neglected the uniqueness and diversity of historical culture from south-east Asia, leaving a superficial acquirement of culture and only caring about business profits. To understand a culture, people should remove the Ethnocentric concept. Therefore, when National Taiwan Museum runs through all the projects, it has to provide the most authentic records with the collaboration of new immigrants, professionals, and overseas scholars and promote the mutual understanding of both groups by holding all kinds of activities, seminars, and museum tours.

References:

- Christopher Goscha(2018)。越南:世界史的失語者。聯經出版。

- John Thomson(2019)。十載遊記:現代西方對古東亞的第一眼:麻六甲海峽、中南半島、臺灣與中國。網路與書出版。

- 社團法人中華民國南洋臺灣姊妹會、胡頎(2017)。餐桌上的家鄉。時報出版。

- 《越南才子樂╳歌籌演唱》│2017亞太傳統藝術節

- 2019越南驚艷—越南無形文化資產國際交流展演

- 中央社報導:越南無形文資展台中開鑼 水偶之舞揭序幕

- Rie Nakamura (2005). Ethinicity of the Cham in Vietnam. Jebat: Malaysian Journal of History, Politics and Strategic Studies, 32. pp. 73-88. ISSN 2180-0251.